The Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) has been cutting the cash rate this year in an attempt to generate higher inflation as measured by the Consumer Price Index (CPI). The RBA’s view is that to meet its inflation target of 2-3%, it needs to generate a tighter labour market to spur higher wages and greater expenditure by households. Reducing the debt burden on households and businesses should help in this goal.

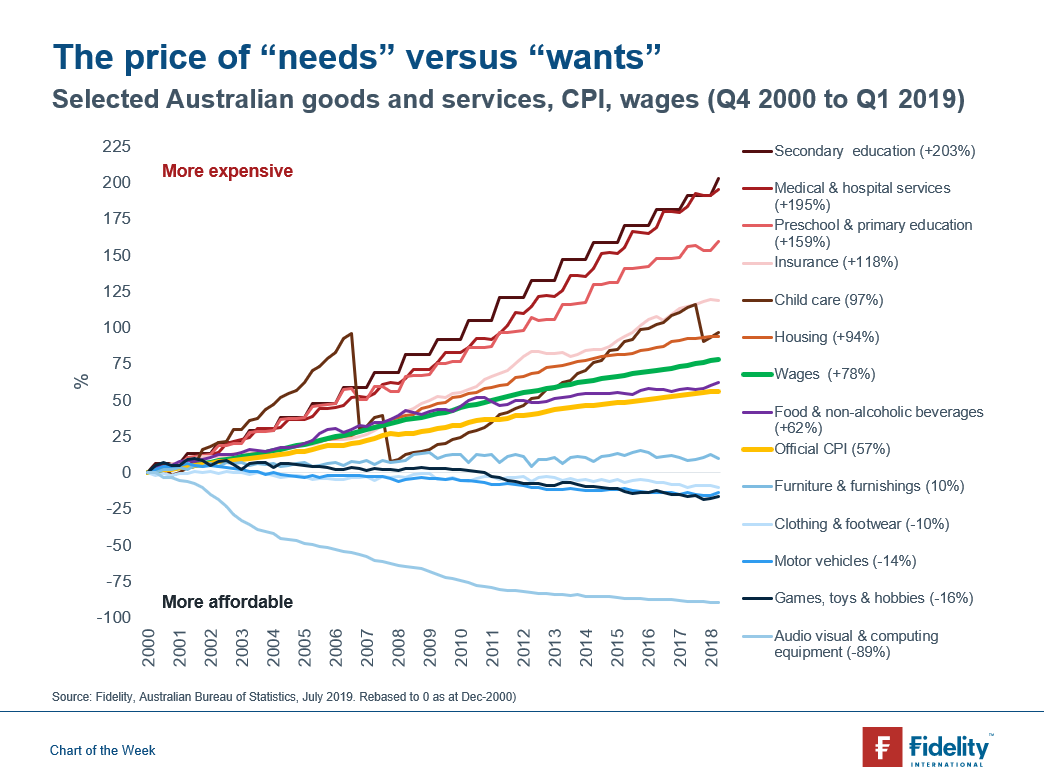

Whilst the CPI is generally seen as the most comprehensive measure of inflation within an economy, it is acknowledged that it is not a true cost-of-living measure. The compilation of a true cost-of-living index is just too difficult to do for statistical agencies because different people buy different things. However, we can get an understanding of the price pressures that Australian households face by looking at the underlying sub-categories of the CPI. In this sense, it is possible to identify the price of household “needs” like food and housing, versus the price of household “wants” like a new computer or toys.

Looking at the long-term (Q4 2000 to Q1 2019) price trends within the Australian economy, it can be observed that there has been significant inflation in household “needs” such as secondary education (+203%), medical and hospital services (+195%), and housing (+94%). The inflation in these categories is far greater than both the wage growth over the same period (78%) and the official CPI (+57%). On the other hand, the category of clothing and footwear (-10%) has experienced deflation. Turning to household “wants”, the prices of motor vehicles has fallen (-14%), as has the audio visual and computing equipment (-89%) category. These categories face structural deflationary pressures, as newer products are generally of a higher quality. As a result, statisticians quality adjust these categories to ensure continuity in the basket of goods and services over time.

The investment implications for Australian households are large. It may not be enough for some Australian households to protect their standard of living from rising costs to own assets that generate returns in-line or slightly above the official CPI. Additionally, cash no longer generates a positive real return (which accounts for inflation), and yields on Australian government bonds are at all-time lows. As a consequence, the average Australian investor will have to accept more risk within their investment portfolios in the hope of generating higher returns. This is especially the case if the cost of household “needs” continue to grow at an accelerated rate relative to the official CPI in coming years.