Can Asia’s economic tiger save the cycle, or will its soaring debt bring the world’s economy down? Keen to avoid a financial meltdown, China’s authorities have brought an end to credit growth, reducing the risk of a crisis but creating a drag on global growth. And if there were another global crisis, China would not intervene again to cushion the blow.

The end of easy credit

Unprecedented central bank intervention has put a floor under the global economy, and led to one of the longest bull markets on record. But the ultra-low interest rates of the past decade have led to soaring debt, potentially laying the seeds for the next crisis.

In contrast to the past few decades, it is the developed world that has seen the largest increase in debt, to a staggering 390% of GDP.1 Yet there is one major exception: China.

Interventionist Chinese policy makers have successfully reined in runaway growth, time and again disproving fears of a hard landing. Under their vision, China is rapidly transforming from an industrial, export-led powerhouse to a modern, technology-based, consumer-driven economy - and from a rural to an urban nation.

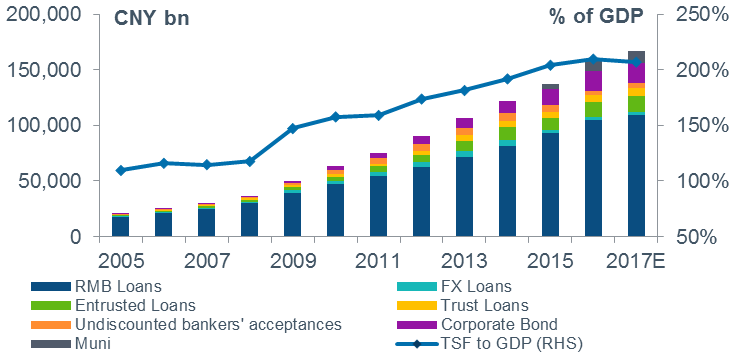

Credit growth powered much of the fiscal impetus that made this possible, and without it, the outcome might well have been very different. But the authorities are now increasingly concerned about the systemic risks of excessive leverage, and are deliberately slowing credit growth. As chart 1 shows, despite lower economic growth rates, total debt is no longer growing as a share of GDP. The impact will be felt globally.

Chart 1: Managing a tightrope between growth and debt

China's debt has risen substantially over the past decade

TSF: total social finance (total debt). Source: Fidelity International, PBOC, WIND, September 2017.

Chinese property sales feed global commodity markets

Property markets have been the first to feel the cold draft, which will, in turn, affect global commodity markets.

Chart 2 shows how total adjusted credit has been slowing all year and still has not troughed, in a marked change from the expansionary stimulus during 2016. Property sales have held up longer in this cycle than in previous ones but are now also falling and the latest data have been particularly disappointing.

Chart 2: Chinese credit growth is slowing, dragging down property sales

.png)

Property prices: three months moving average. Source: National Bureau of Statistics of China, Bloomberg, Fidelity, November 2017.

Tightening monetary conditions like these act as a bearish lead indicator for commodity demand.

Although it is unusual for a single (national) demand driver to explain price movements for an entire (global) asset class, Chinese property sales act as a relatively strong lead indicator of commodity prices, because building activity accounts for a good chunk of commodity demand. Steel, for example, is used in construction, while copper is important for construction, grid connections, and white goods. China’s market is large enough to affect demand globally. So when property sales are negative, it is rare for commodity prices not to be falling too.

Chart 3: Could global commodity prices be heading lower?

Commodity prices based on CRB index. Property prices: three months moving average. Source: National Bureau of Statistics of China, Bloomberg, Fidelity, November 2017

Chart 4: And could this be a sign of slower global growth?

Commodity prices based on CRB index. Source: Datastream, Bloomberg, Fidelity, November 2017.

Global growth may suffer

And it’s not just housing; credit growth in China has other effects as well.

The 2016 stimulus led to an export boom, providing another source of growth for the country that spilled over into the rest of the world. Exports are still doing well, fuelled by strong economic growth abroad, but the credit stimulus is fading and when the mechanism goes into reverse, exports could suffer, eating into GDP growth. In short, not only does the contribution from property then turn negative, but exports stop flattering GDP growth.

There are other factors to watch in the commodity market, including low supply growth in major commodities beyond 2019 and Chinese supply side reforms. In 2013, for example, a supply glut prevented commodity prices from rising despite a strong property cycle. On balance, however, we believe continued financial tightening and property market deceleration will act as bearish forces on the global commodity cycle, and may be indicative of slowing growth ahead. Even if China started stimulating credit today, property markets in the country would still record at least two quarters of flat or declining activity because it takes time for such stimulus to work. And stimulus may not be politically palatable. In President Xi Jinping’s words: “Houses are for living in, not for speculation”.

History is on his side. Chinese leaders have been more effective in their second term, including President Hu Jintao who oversaw the RMB 4 trillion (nearly US$600 billion) stimulus package after Lehman’s collapse.

The signs are that President Xi will follow this pattern, consolidating power in his second five-year term with a renewed focus on implementing his policy agenda, including much-needed structural reforms and the deleveraging of state companies. These measures aim to ensure that the 6.5% target GDP growth rate is not just achievable, but also sustainable.

China is neither willing, nor able, to come to the rescue

During the global financial crisis, China’s huge stimulus spending helped temper the effects of the global downturn. But China today has neither the same appetite nor the ability to play a similar role. Any investor who is concerned that global markets could be heading for a correction should not expect China to cushion the blow this time around.

Ten years ago, in the throes of the financial crisis, China came to the rescue with an enormous fiscal package that acted as a global shock absorber. Infrastructure spending bolstered domestic demand, but it also put a floor under commodity prices globally and lifted fears of deflation, providing a life line to both developed and emerging economies.

In addition, China’s decision not to let its currency weaken to help absorb the shock resulted in a loss of competitiveness for the country’s export sector that became evident as its current account surplus plunged.

These measures worked because China was more dependent on global trade at the time of the crisis than it is today, with exports then contributing as much as 37% of its GDP, compared to less than 20 percent today2. When global trade went into free fall, Chinese policy makers boosted domestic demand in riposte.

Today’s China is different: much less export-driven and more focussed on consumption and services. Changes to China’s currency policy mean the renminbi, while still not freely convertible, responds more closely to internal and external economic pressures. China’s increased reliance on its own consumers to support growth will taper its motivation to act in the same bold way.

Nor does China have the same ability to act without exacerbating concerns about its debt, which has more than quadrupled in the past decade. Not only does this hamper the country’s ability to deliver another vast fiscal stimulus package, but any additional debt it takes on now will also have diminishing returns. Today it takes substantially more units of new credit to generate an additional unit of GDP than a decade ago.

Managed risk, but a different China

China’s ruling authorities have deftly managed to slow growth without triggering a ‘hard landing’ and have modernised the economy in the process. Their interventionist approach significantly reduces the risk of a near-term debt crisis in China, which should be of comfort to investors, but it could also lead to a drag on global growth in 2018.

Just as important is that this new China is much more inwardly focussed. Its technology companies are world-class and its citizens’ modern amenities are now homemade. If global markets or economies take a nosedive, China’s fiscal and monetary policies will no longer be there to prop up global demand.

1Institute of International Finance (IIF), April 2017

2World Bank, October 2017: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NE.EXP.GNFS.ZS?contextual=default&locations=CN