ESG investing seems all the rage, but what does this focus on environmental, social and governance criteria actually mean? ESG practices among investors and institutions vary widely, and what is seen to constitute ESG investing has evolved over time; today’s approaches to ESG investing range from simple exclusion lists to activist strategies.

We think the absence of a unified definition may not matter all that much in the grand scheme of things - and it will not halt progress in ESG investing. Having said that, it does pose a challenge for investors who need to decide on their own definition and criteria.

What is ESG?

What is ESG? Finding an answer to that question is much harder than it ought to be. Environmental, social and governance factors cover an extremely broad range of issues from avoiding investing in tobacco companies to financing clean water initiatives. The fact that different labels such as sustainable, responsible, ethical and impact investing all fit under the ESG umbrella complicates finding a definition that encapsulates all the different facets of ESG.

The concepts underpinning ESG have also evolved over time. A hundred years ago, responsible investing was mostly about religious beliefs influencing the choice of investments. Now it’s also about people’s perceptions of themselves and their role in society informing their investment framework. ESG’s beginnings were largely based on exclusion - avoiding the asset classes and sectors deemed to have a negative effect on society - but in recent years it’s extended to modern-day activism, where investors directly intervene to enact positive change. Today, ESG is considered by some as an asset class and an investment approach in its own right.

Investor motivations for pursuing ESG vary widely, ranging from the already mentioned moral and religious beliefs to regulatory and legislative requirements, public and client pressure, and economic reasons. Some of the issues that ESG-aware investors think about today are detailed in the diagram below.

From this starting point we unpick the complexities of what constitutes ESG and try to pin down a universal definition by asking why ESG matters, what’s driving the ESG trend and what the different approaches to it are. In doing so, we also highlight the range of interpretations of ESG, and that the discipline requires investors to think carefully about their own policies and beliefs.

Environmental

- Climate Change

- Greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions

- Resource depletion, including water

- Waste and pollution

- Deforestation

Social

- Working conditions, including slavery and child labour

- Local communities, including indigenous communities

- Conflict regions

- Health and safety

- Employee relations and diversity

Governance

- Executive pay

- Bribery and corruption

- Political lobbying and donations

- Board diversity and structure

- Tax strategy

Why does ESG matter?

There are two broad schools of thinking when it comes to why ESG matters; one starts from the role of investors in society and the other focuses on risk management.

Many investor groups including pension funds, charities and endowment funds see their role as more than just return-seekers. They are conscious that funding our retirements, financing societal initiatives and contributing to the cost of education, can lend them a function within wider society.

With this responsibility comes influence. These investor groups manage significant pools of capital; directing this capital gives them a substantial amount of authority. They decide how and where they want their funds allocated, and can choose to favour schemes that aim not to have a negative effect on society or those targeting a positive effect.

The other major philosophy behind ESG is rooted in risk management. Investors who take this approach incorporate ESG factors into their investment process to help mitigate risk. For example, a potential investment in a company with low ESG standards could expose the portfolio to a variety of risks faced by the company in the future, such as worker strikes, litigation and negative publicity etc., resulting in lower future returns. For investors, monitoring the ESG credentials of an investment can lead to better risk-based judgements.

This is not a divergence from the traditional investment principle of maximising shareholder value - it’s an evolution. In the early 2000s, there was some debate over whether the fiduciary duty of asset managers included considering non-investment related indicators such as ESG characteristics. A large body of research since has led to an overwhelming consensus that ESG factors do indeed play a part in the performance of investments. By considering ESG, investors may be able to deliver better risk-adjusted returns.

What factors are driving ESG?

The primary driver of the growing focus on ESG is access to information. The proliferation of 24-hour news channels, the internet and social media mean that the public has an extraordinary amount of information available at its fingertips. It’s not only an instant news world, but it’s also a global news world - we can find out rapidly what is happening almost anywhere in the world.

Armed with this transparency, public scrutiny is at an all-time high, and people power is changing how the investment world behaves. Companies understand the value of their brand and have a heightened sensitivity to public opinion to avoid risking damage to their reputation. The rapid response by a number of companies to distance themselves from the National Rifle Association (NRA) in the wake of a mass shooting in Florida in February 2018 demonstrates this clearly. It was the first time this happened after a mass shooting, and it was largely down to companies sensing the changing public mood.

This public scrutiny affects how institutional investors direct their capital, which in turn influences how asset managers deploy funds and engage with companies. But the relationship between institutional investors, asset managers and companies isn’t one way. They often have long-term partnerships and influence and inform each other. So in practice, the drive towards ESG can come from institutions, asset managers and industry.

One important aspect of the increasing access to information is the availability of data. This has made it practical to incorporate ESG factors into the investment process. Regulatory frameworks have improved, companies disclose more ESG information, ESG investment metrics and tools are proliferating, independent third-party agencies provide ESG ratings, and new ESG indices allow for portfolio benchmarking. And an increasing body of research explains how to incorporate ESG factors into decision making.

Turning points

It’s worth highlighting a few turning points in the history of ESG investing which had a significant effect on how the discipline developed.

- The economic boycott of Apartheid South Africa was first proposed in 1962 by UN Resolution 1761, which called for imposing economic sanctions on South Africa. In 1977, the Sullivan principles advocated institutional investors withdraw direct investments from the country. By the mid-1980s, capital flight reached scale, and as the South African rand fell, inflation rose to over 18% in 1985, and the government introduced capital controls. This ESG approach of divestment has largely been out of favour for much of the intervening years, but has been re-introduced by NGOs more recently. The technique was on full display in February against corporations with connections to the NRA.

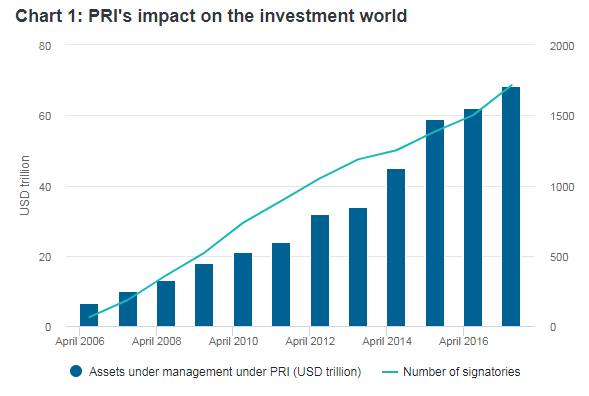

- The Principles of Responsible Investment (PRI) aimed to counter the argument put forward by some investors that their fiduciary responsibility to clients meant that they could exclude non-financial indicators in the investment process. The PRI argued against this limited understanding of fiduciary duty and launched a guide to help investors integrate ESG techniques into their equity investing process. As of April 2017, there are more than 1,750 signatories to the Principles from over 50 countries, who are collectively responsible for nearly USD 70 trillion.

- The UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDG), published in 2015, listed 17 objectives and 169 associated targets to transform the world by 2030. Although these principles are not legally binding, they have had a pervasive influence and are increasingly informing ESG policies of many institutions including governments, universities and financial entities.

- The Paris Climate Agreement is the world’s first comprehensive climate agreement, and entered into effect in November 2016. It’s legally binding in forcing governments to accept and cater for the goal of keeping global warming this century to below two degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels. The agreement has spurred many climate-based initiatives and accelerated the move away from fossil fuel-based vehicles. The US’s withdrawal from the agreement cannot take effect until November 2020 at the earliest, after the next presidential election. And despite the government’s positon, many states and corporations in the US have publicly committed to the climate targets.

Source: PRI, April 2017

What are the main approaches to ESG?

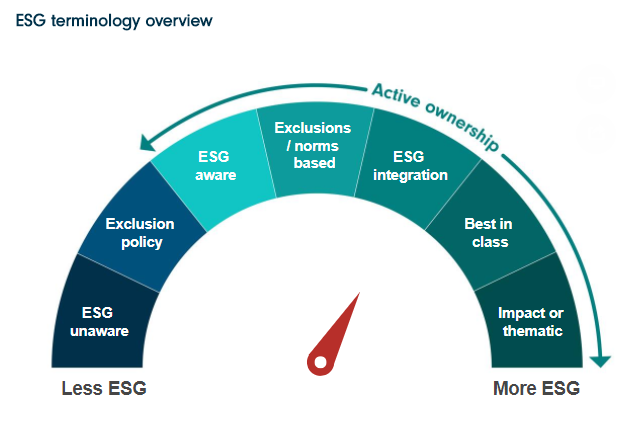

Investors can implement ESG considerations into their portfolios in a host of ways, stretching from active ownership to impact investing. One way to think about the different approaches is as a dial, from ‘less ESG’ to ‘more ESG’. The diagram below shows how this can be done - it is a rough guide and there are gradations within, and overlaps between, categories.

For illustration purposes only. Source: Fidelity International, March 2018

ESG unaware - This is a stage where investors place no positive value on ESG-related issues. They may consider certain risk management or regulatory factors somewhat relevant to ESG such as the potential for environmental litigation, but this is based on avoiding loss rather than the positive shareholder benefits of incorporating ESG into investment decisions.

Exclusion policy - This excludes investment sectors which are contrary to the investor’s ESG specific criteria, such as avoiding weapons or tobacco stocks, or investments in countries with poor human rights records. Outside of these excluded categories, investors apply a standard investment approach.

Active ownership - Investors seek to influence companies on many different levels so this includes a broad spectrum of interaction with company boards and straddles many categories. Investors can take an engagement approach where they monitor the ESG performance of companies and engage in constructive shareholder dialogues to ensure progress. A consulting approach is a particular form of engagement where larger institutional investors and shareholders are able to pursue ‘quiet diplomacy’, attempting to influence the company through regular meetings with top management, exchanging information and developing a trusted adviser relationship. Activism is the most aggressive form of engagement. It is a pressure-based technique, involving strategic voting in support of a particular issue or to bring about governance changes. This approach can be pursued publicly to apply more force. Increasingly, we are seeing investors use activist methods for environmental and social-related issues, rather than purely governance.

ESG aware - Investors recognise the positive contribution that ESG considerations can make to investment outcomes. This is a broad category and there are varying degrees of the level and systematic recognition and incorporation of ESG elements into investment decisions.

Exclusion / norms based - This is a more comprehensive type of negative screening that excludes investments in companies which do not meet widely accepted norms such as the UN Global Impact principles, Kyoto Protocol, or the UN Declaration of Human Rights.

ESG integration - The consistent fundamental analysis of environmental and social issues to adjust forecasts of key security price drivers, in order to identify additional sources of risk and opportunity, and deliver better overall investment decision-making. Statistical methods can also be used to establish a predictive correlation between the sustainability aspects of a company’s performance and financial factors.

Best-in-class - Investors actively select companies to invest in based on a set of ESG criteria or choosing from a sub-set of the best practitioners in a sector. In practice, this can involve ranking the potential investment population by the criteria, then selecting the best performers from each characteristic or picking a number of investments that feature in the top group of the ranking.

Impact or thematic - This refers to investments made with the intention to generate measurable and beneficial social or environmental impacts alongside a financial return. This differs from traditional philanthropy because it intends to earn a financial return. It often follows themes such as renewable energy, water treatment, education providers etc.

These approaches to ESG demonstrate what a broad church it is. One element that binds all these forms together is the careful consideration, by investors, of environmental, social and governance effects on stakeholders. This requires investors to integrate, to some degree, ESG factors into the investment process. Such integration could take the shape of a separate ESG advisory group informing the investment decision makers, or an ESG function embedded in the investment process. Either way, ESG investing requires investors to conduct, intentionally and systematically, an assessment of relevant risks and opportunities as part of their financial analysis, in order to allocate capital in a society-conscious way.

Conclusion

The closest this takes us to a definition of ESG is a statement about assessing risks and opportunities within the investment process in order to allocate capital in a society-conscious way. We don’t have a more specific, unified ESG definition - but do we even need one?

Investors practice their craft differently according to the asset class they operate in, their objectives, their resources, and the investment environment and market infrastructure prevailing at the time. As a result, there has always been a variety of investment styles and approaches to making investment decisions in the non-ESG world. Indeed, this range of approaches can inject diversification and risk management benefits into portfolios. So instead of seeking a universal definition of ESG, perhaps it’s more productive for investors simply to understand a providers’ approach to the discipline, and decide whether that aligns with their own objectives and beliefs.

The ESG landscape is evolving, in part because of the different voices and entities informing the discussion. Public scrutiny, governments, supranational institutions, academics, asset owners, asset managers and corporations are all presenting unique points of view. We think robust debate is healthy, and likely to lead to better ESG analysis, implementation and outcomes in the long term, just as it has in other corners of the modern economy.

External factors to the debate such as the progress of technology and data, and events such as the BP oil disaster in 2010 or the Wells Fargo mis-selling scandal in 2016, undeniably have an impact on the ESG conversation. The common criticism that ESG becomes merely a luxury when the market turns downwards perhaps had an element of truth to it in the past. But it’s also reductive to say that ESG is reactionary. Not only is there data supporting its role in investment returns but it’s also becoming increasingly institutionalised in financial analysis. ESG, just like in the decades before, is not going away, but is here to stay and continuing to evolve.