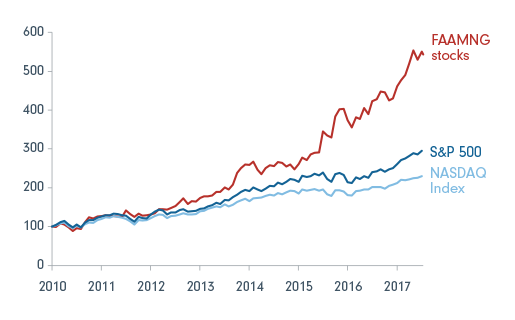

This is a difficult cycle to understand. The shares of Facebook, Amazon, Apple, Netflix, Microsoft and Google have all boasted strong returns over the past year, together accounting for almost half of the total return of the S&P500 despite making up only 15% of market capitalisation. Is this a bull market or a bubble?

Maybe it’s misleading to compare what’s going on to earlier booms. In the current market, it is investors’ fear of losses, as against their desire not to miss out on gains, that is fuelling price distortions. And new investment vehicles and strategies are amplifying the effect. Drawdown risks may hide in unexpected corners.

History doesn’t always rhyme

The saying goes that history doesn’t repeat, but it rhymes. Yet today’s exceptional growth in US technology stocks is quite different from the late 1990s bubble, when media and telecommunications companies took the lead amid a flurry of highly priced IPOs.

For one, it is by no means a global phenomenon. European equity markets, for example, are dominated by ‘old economy’ companies - oil, tobacco, pharmaceuticals and banks. In addition, capital investment today pales in comparison to the 1990s boom, which was about physical infrastructure as much as it was about software, creating the modern telecommunications infrastructure required to carry internet services (even if much speculative capital went up in smoke).

Funding is different too, as young companies remain in private hands for much longer than last time, when the equity market proved a willing provider of capital to new business ventures, shining a light on egregious valuations of early-stage companies.

Can the largest tech stocks continue to outperform?

FAAMNG: Facebook, Amazon, Apple, Microsoft, Netflix and Google. Price return rebased to 100 on 01/01/2010.

Source: Fidelity International, Bloomberg, August 2017.

Once bitten, twice shy

If the last tech boom does not provide a useful analogy of what is going on, we need to look elsewhere for explanations.

In his recent investment letter, ‘There They Go Again…Again’, the legendary investor Howard Marks sounds a note of caution about the level of asset prices right across the spectrum, from equites to high yield notes and emerging market debt. He describes an environment where “pro-risk behaviour is commonplace.”

I agree that the impact of market participants’ behaviour tallies with Marks’ view, but I think that we have reached this point of the cycle in asset prices almost entirely without the optimism or risk-seeking behaviour that Marks warns of.

In fact, I think investors' motives may be quite the opposite: still scarred by the financial crisis they have a powerful desire to avoid capital loss, even over the short term, and a need for stable returns from that capital. A broad-based belief that the outlook for the global economy remains highly uncertain - a perception amplified by a political landscape of unprecedented instability - doesn’t help confidence.

Whereas most bull markets and bubbles are driven by investors’ focus on capital gains, and their subsequent fear of missing out, I think that this market has been driven by an overwhelming desire for capital security or perhaps modest gain. Securities that offer certainty of yield (irrespective of the underlying assets) or certainty of growth (the tech mega-caps) have attracted the largest flows. These trends have persisted largely unchanged for years.

Yet collectively, this risk-averse behaviour has driven asset prices to alarming levels. Where capital flows in, price increases duly follow. So prices of apparently safe, stable assets have soared, meaning long-term asset owners face a remarkably challenging market, where it has never been so risky to be safe.

New marginal buyers

If I am right and markets have been driven by an excess of prudence, then where is the marginal buyer coming from? To quote another legendary investor, Warren Buffet, “what the wise do in the beginning, the fools do in the end”. It’s common for asset price booms eventually to draw in investors who were initially sceptical. This was certainly true of the original tech boom, when the sceptics on the sidelines were taking on ever greater amounts of benchmark risk and career risk until most were forced to join the party.

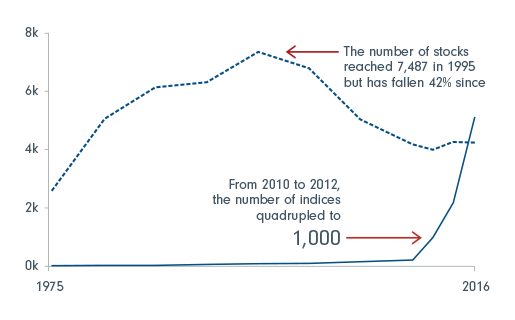

But this time, it is not just sceptics joining the fray and pushing prices ever higher. More important is the boom in new, non-discretionary vehicles such as passive funds, ETFs and quant strategies. Again, it is worth highlighting that these allocation decisions are usually not founded in a ‘risk-on’ mind-set, but instead represent a desire for low-cost access - nothing more.

The number of indices is growing exponentially

Source: Fidelity International, Bloomberg, August 2017

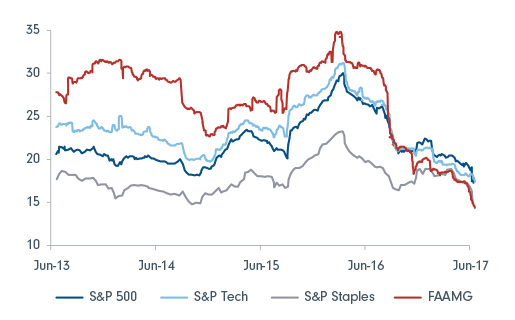

The cautious investor mind-set is also reflected in the growth of low-volatility strategies. They aim to achieve modest absolute returns through investing in low-volatility assets, reducing the risk of a loss of capital. Yet when investors flock towards particular assets over any length of time, the reported volatility of those assets declines, because drawdowns are contained by persistent buying.

What appears to be happening now is that the sustained inflows into tech mega-cap stocks in the US are fuelling a self-perpetuating cycle. Remarkably, these stocks have a realised volatility lower than consumer staples or utilities.1 This will have led to additional demand from minimum-volatility quant strategies and ETFs as well as market capitalisation-based passive strategies.

Understanding this helps to explain not only the performance of the tech mega-caps in the US, but also why the dominant market capitalisation structures in other markets have persisted.

FAAMG realised volatility is not only below the SPX, but also below staples (6 month realised volatility, %)

FAAMG stocks are: Facebook, Amazon, Apple, Microsoft, Google.

Source: Goldman Sachs, Fidelity International, June 2017.

Too risky to be safe?

There is little doubt that investors would do well to heed Marks’ warning about many asset prices. It may be true, as he points out, that value investors have a tendency to sound the alarm early, but there are certainly enough examples of allocations shifting to riskier assets - and of riskier assets becoming mainstream - to give us pause.

But, I think it is also important to consider the dominant investor psychology - the motives of significant actors - to assess the gains made in recent years. In contrast to the previous boom, it is a broad-based flight to safety and capital loss aversion that is fuelling the rise in US tech giants’ shares.

This leads me to very different conclusions about where the risks of material capital loss lie, if indeed we are approaching the end of the post-financial crisis bull market.

It could well be that securities which are unattractive to those with a strong aversion to capital loss may paradoxically prove to be the most resilient. In other words, if the price of avoiding volatility is elevated, there may be an economic rent for taking on the volatility that others reject.

Views from Amit Lodha, Portfolio Manager Fidelity Global Equities Fund

- I think Paras makes an excellent point around crowding and the fact that sentiment is very one sided in technology. We have been mindful of that (Why I took a break from Facebook) and our overweight in technology and software is being gradually reduced as on a bottom basis risk reward is not justified given valuations have risen faster than change in either delivery of actual free cash flow or material increase in forecasted cash flows.

- I believe ETFs are the major force in the market and flows are driven more by the need for 'exposure to a theme' rather than a fundamental evaluation of the merits of the investment case and valuations.

- During market corrections, correlations increase and the potential for the most hurt is where investors are crowded and conversely least where there is limited investor interest. If you make the case that then next correction will be driven by changes in the bond market and interest rate environment then the hitherto safety stocks or bond proxies (such as consumer staples, utilities, large cap pharmaceuticals and FAANG) would be most at risk whilst the pariahs (such as energy, materials and to an extent financials), which have low investor crowding, should do well.

As Paras says, each market correction is different so we wait and watch.