by James Hickling, Investment Commentator at Fidelity International

June 2016

Airbnb’s challenge to hotel chains and Uber’s clash with taxi firms are perhaps the best examples of industries where technological advances have undermined barriers to entry and slashed start-up costs so much that the old order is threatened. It could well be that finance is the next industry to be disrupted.

A telling indicator of the disruption heading towards finance is that global investment in fintech ventures soared from US$4.1 billion (A$5.5 billion) in 2013 to US$21.2 billion just a year later.[1] Expectations are building that significant change looms for an industry where many incumbents, particularly big banks, are unpopular, especially among young people.

Already challenger banks with potentially disruptive new models have appeared, such as proposed UK-based smart-phone bank Mondo, which offers phone-based banking with digital spending and budgeting analytics. Mondo caught the attention of investors with a successful round of capital raising (of 6 million pounds or A$12 million) in 2016, partly via crowdfunding, another disruptive threat to traditional finance. (Mondo’s raising of 1 million pounds in 98 seconds is touted as the fastest crowd-funding ever.) Atom and Tandem are two other “next-gen” UK banks seeking to challenge established players.

Challenger banks are just the start of the disruption heading the way of long-standing banks. Advances in technology are occurring in payments, crowdfunding and blockchains – not necessarily by doing new things but by doing old things in a more efficient, productive manner. Emerging countries are ripe for fintech because they are relatively unbanked and their banking sectors are less advanced. Traditional companies can see the opportunity and are investing in fintech too. Customers are embracing it. The company or companies that become equivalents to banking that Amazon.com is to retail will become some of the biggest commercial names of the 21st century.

To be sure, no explosive fintech advance has surfaced yet. Fintech startups often seem to be competing with each other for niches rather than scaring established players. Some fintech companies that raised money have already collapsed; there’s nothing easy about disrupting a centuries-old business model. Finance is unlike other industries to the extent the state takes a critical, even domineering, role due to banking’s lifeblood function in the economy and to protect savers. Disruptive entrants have to reckon with large incumbents with political power. In addition, ventures like bitcoin and the enabling blockchain technology challenge the state’s monopoly on money and payments. Many say fintech is little more than hype so far. Still, plenty of people backed by significant money are aiming to disrupt banking as we know it. Some surely will succeed in ways we can’t imagine yet.

Modernising payments

One of the most basic functions of everyday finance is payments and alternative systems are already gaining traction. About 44% of US millennials are using mobile payments and 13% of them use digital currencies.[2] US mobile payments are expected to reach US$142 billion in 2019, by Fidelity estimates. A trend away from physical cash is evident, supported in part by government desires to crack down on tax evasion. The trend justifies, in part, the imposition of negative rates in Europe and Japan because e-money cannot be stashed like cash.

The popularity of mobile-phone banking is driving faster payment development; there’s not much advantage to mobile payments if settlement takes three days. Online retailers are accustoming us to one-click purchases and receiving the goods in no time – an immediacy that contrasts with the slow money transfers taking place in many countries. Faster payments could help smaller businesses given the importance to them of cash flow. Incredibly, nearly 50% of payments by US businesses are still made by cheque. The US interbank system, which has operated since 1974, still takes two to three working days to settle transactions. This is due to the fragmented nature of the US banking industry, high levels of regulation and tight internal controls.

Changes, however, are afoot in the US. The Federal Reserve is working on plans for a new system, which could be implemented in five to 10 years. The system could be modelled on the UK’s Faster Payments Service, introduced in 2008, that has reduced customer transfer times to typically a few hours. Just as mobile transfers have encouraged faster payment development, so speedier payments, in turn, can catalyse new mobile-finance solutions. New platform providers, unencumbered by legacy IT systems, will be well placed to profit, particularly given the high regulatory costs shouldered by large money transmitters.

Payment innovation isn’t just being pioneered by small firms and startups. Visa, for example, has arguably become far more like a tech stock than a financial stock because of the US credit-card giant’s emphasis on new payments technology and the development of merchant analytics. And while Europeans may take contact and contactless card payments for granted, globally such methods account for only about 33% of card-based transactions. The US is ripe for greater penetration in this area.

Many emerging countries are at the forefront of alternative payments due to their largely unbanked populations. (About 50% of the world’s population is unbanked.)[3] In particular, the gap between relatively-high mobile-phone ownership and low access to financial services has encouraged the development of mobile payments. M-Pesa, first launched in Kenya in 2007 by Safaricom, is probably the most successful of these. M-Pesa now processes US$24 billion in payments a year, equivalent to about half of Kenya’s GDP, and Kenya now has more mobile payments than any other country, according to Goldman Sachs estimates. In China, nearly 10% of all payments are now made using Alipay, which is an online system combining payment, lending, deposit and other functions. About 80% of bitcoin volume is exchanged into and out of Chinese yuan. Emerging markets are effectively skipping the credit-card stage of payments evolution by going straight from cash-based societies to mobile payments.

Blockchain promise

The buzz around bitcoin has subdued somewhat, in part, because its volatile price action calls into question its use as money. But the hype around the so-called blockchain – the distributed ledger on which bitcoin is based – is reaching fresh heights. The hope is that it will result in significant settlement and cost savings across financial services. At the moment, trading in many securities relies on negotiated contracts between buyers and sellers. It still takes almost 20 days on average to settle syndicated loan trades. The cost to the finance industry of clearing, settling and managing post-trade environments is estimated at between US$65 billion and US$80 billion a year.[4]

A blockchain allows instantaneous trading and verification without a central ledger. Using decentralised networks for payments and settlement could help banks save billions of dollars a year – potentially US$15 billion to US$20 billion a year from 2022, according to Spain’s Santander Bank[5] – by improving and outsourcing slow and inefficient back-office settlement. This would cut the amount of collateral held up in global payment systems and reduce transaction costs. Blockchain has been described as “email for money” as it could expand flexible payments across industries. If people had, for example, the option of an instant 5 cent payment to read an online article, this could help solve the problems the media has in monetising online content, by doing away with the hassle and cost of signing up for annual subscriptions.

Big money is flowing into blockchain development. Success could result in significant profit gains across the financial sector. Such advances would open up for sale on the internet a host of low-value products that had previously been excluded because collecting payment was uneconomical, even to the point of costing more than the item purchased. Investment opportunities could, thus, include successful blockchain developers as well as third parties that can integrate the technology into their business models.

Savvy lending

Much innovation, too, is happening on the lending side of banking. The use of big-data analytics, combined with internet marketing and distribution, is allowing alternative lenders to take a growing chunk of the loan market from banks. The years since the global finance crisis have seen strong regulatory pushes for banks to raise their tier-one capital ratios, in order to make them more shock-proof. This has for the most part been achieved, but at the cost of banks reducing lending to riskier borrowers.

As a result, alternative lenders have been stepping into the riskier-lending space vacated by banks. Record low interest rates have encouraged credit creation, as investors turned to higher-risk investments in the search for yield and as lenders became more comfortable with borrowers’ abilities to make interest payments. Goldman Sachs estimates that across the six consumer-orientated lending sectors it views as most promising for alternative lenders about US$7.8 trillion (20% of the market) could leave the banking sector.[6]

Peer-to-peer (or P2P) lending, which connects lenders to borrowers directly, is another face of disruption. In return for lending at a fixed rate for a set period, lenders charge higher interest rates than they would receive by depositing their money in a bank, while the borrower enjoys a lower rate than it would have paid a bank. This win-win situation is thanks to disintermediation – removing the banking middleman and associated operating expenses such as costly branch networks. The average savings bank in the US had operating expenses of 5.3% of average loans outstanding in the third quarter of 2014 compared with a figure for the US-based peer-to-peer LendingClub of just 1.7%.[7]

It sounds enticing, but there are grounds for caution. For starters, much of the information provided by borrowers isn’t verified. Recent regulatory filings in the US by peer-to-peer lender Prosper disclosed that it only verified employment and/or income for just 59% of loans from 2009 to 2015.[8] LendingClub’s latest annual report notes that: “We often do not verify a borrower’s stated tenure, job title, home ownership status, or intention for the use of loan proceeds.”[9] Other analysis suggests that nearly a third of the firm’s outstanding loans during the first nine months of last year were issued without income verification.[10]

On top of this, nearly all of peer-to-peer lender revenue comes from origination; only a fraction is tied to loan performance. There are thus grounds for suspicion about the quality of many loans, especially given that these lenders haven’t been through a complete credit cycle yet; institutional lenders tend to use through-cycle default rates as a base line for their interest rates. Investors could be significantly undercharging themselves for the risk associated with many of these loans – especially given the lack (yet) of a significant secondary market.

Useful crowds

Another promising area of fintech is the crowdfunding that Mondo tapped into. The internet-enabled ability to raise a significant amount of money from a vast number of people is changing the way people and businesses market products, services and ideas. It has seen significant growth in recent years across a variety of industries. About 10% of the films accepted into the Sundance, SXSW and Tribeca Film Festivals, for instance, were crowdfunded via Kickstarter, an arts platform that has funded 101,951 projects by raising US$2.3 billion from 10 million people.

There are two main models of crowdfunding: donation or rewards-based models (common for charity fundraising) and equity-investing platforms. The rise of crowdfunding is partly a consequence of the financial crisis because startups struggled to access funding from cautious lenders. Millennials, who are less likely to own stocks due to their suspicion of the financial sector, are more willing to invest in crowdfunding compared with older generations, largely down to it being deemed an “authentic” experience that allows a greater sense of ownership compared with traditional financial assets. Millennials also have a greater desire for investments to reflect their personal values.

Crowdfunding is a major beneficiary of network effects made possible by social media. An entrepreneur can start a campaign that someone else discovers and pledges money to. The backer is then incentivised to share the campaign across social networks, which drives traffic to the crowdfunding site. This increases the likelihood the campaign will successfully raise the required amount and encourages future campaigns. However, while crowdfunding is opening up funding possibilities for new entrants, it is yet to interest large investors because of the lack of a secondary market for the shares issued and the speculative nature of the startups. That will no doubt change as fintech’s Airbnbs and Ubers emerge over the 21st century.

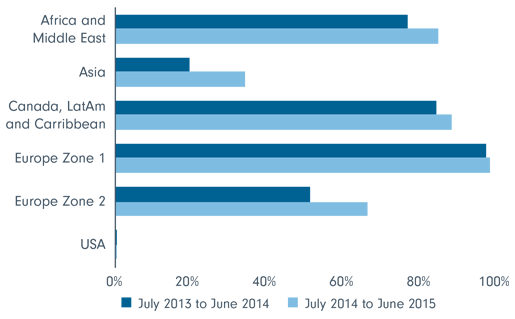

Smart payments card adoption rules

Source: emvco.com, March 2016

Financial information comes from Bloomberg unless stated otherwise.

Important information

References to specific securities should not be taken as recommendations.

[1] Bank of America Merrill Lynch. Thematic Investing. May 2015.

[2] Bank of America Merrill Lynch. Ibid.

[3] Goldman Sachs, Equity Research. 3 March 2015.

[4] Financial Times. “UK start-up claim blockchain breakthrough in payment processing.” 12 October 2015. http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/a2260946-7009-11e5-8af2-f259ceda7544.html#axzz451IEXrAf

[5] Financial Times. “Technology: banks seek the key to the blockchain.” 1 November 2015. http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/2/eb1f8256-7b4b-11e5-a1fe-567b37f80b64.html#axzz451IEXrAf

[6] Goldman Sachs. Equity Research. 3 March 2015

[7] Goldman Sachs. Equity Research. 3 March 2015

[8] Fool.com. January 2016.

[9] LendingClub Corp. Annual report 2014.

[10] Bankinnovation.net, February 2016.