As economic and structural conditions change throughout investment cycles, so do the opportunities for generating returns. This piece examines when and how to combine the various shades of active and passive as external conditions develop.

Active managers spend a lot of their time rummaging through the mass of investment opportunities within a given market, seeking potentially mispriced assets: those whose fundamental value or bright potential has yet to be fully realised. Passive investing, in contrast, is predicated on the idea that indices themselves provide the most efficient access to a broader market.

Because they appear so discordant, the two strategies are often pitted against each other in an active versus passive tug-of-war. In fact, they’re complementary. In the real world, markets are a microcosm of their broader economic, political and regulatory environment. As conditions evolve throughout the course of an economic cycle, so do the forces driving markets.

Sometimes pure beta exposure will provide an adequate return, with marginal room for alpha generation. At another stage, inefficiencies will provide opportunities for skilled active managers to outperform. More often, though, the optimal strategy employs varying degrees of both.

In the context of a typical cycle, what exactly does that mean?

The recovery position

The economic cycle kicks off when the first green shoots emerge from the rubble of a downturn or recession. Growth picks up and central banks loosen their belts, providing further impetus to the recovery. Consumers and corporates take advantage of plentiful credit and economic indicators assume a more upbeat tone.

These optimistic early-cycle days are often accompanied by a sharp market rally as investors pile back in from the sidelines. Risk assets like high yield debt and equities return to favour, while consumption-related themes, as well as the IT, industrial and financial sectors tend to do well.

At this point, passive exposure to an index can deliver decent returns as the ‘rising tide’ of sentiment ‘lifts all boats’. However, some company share prices are punished more than others when markets turn sour, which makes the early stage of a recovery fertile ground for active managers too.

Value investors in particular tend to stand out in this environment, given their focus on uncovering companies with robust fundamentals that are not reflected in their share price. And following a downturn, there are usually plenty of these.

Expanding through the middle

Following the recovery phase, economic growth accelerates, buoyed by accommodative monetary policy, while employment, productivity, demand and consumption continue to expand, exerting upwards pressure on prices. Markets tend to follow suit, supported by positive momentum and abundant liquidity.

Amid widespread confidence in the economic backdrop, assets are typically highly correlated and exhibit low volatility and dispersion; conditions in which passive strategies have historically outperformed. When lower-cost beta exposure delivers attractive and consistent performance, investors are less likely to apportion budget to more costly enhanced-return strategies as the difference between the two becomes marginal.

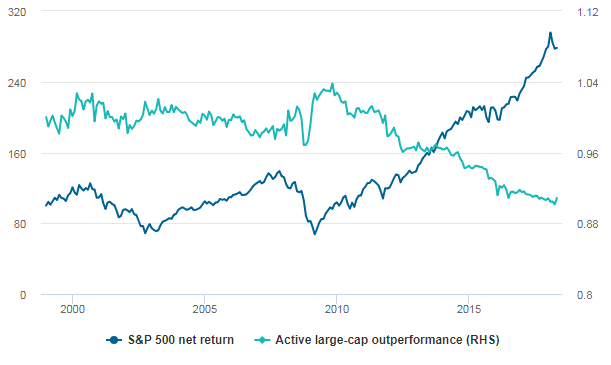

The recent and long-running mid-cycle to 2017, fuelled in part by the quantitative easing programmes of major central banks, is a prime example. In an environment of record low volatility - the VIX average daily closing price in 2017 was the lowest of any year since its launch in 1986 - active managers in many developed markets have found alpha opportunities relatively thin on the ground. Meanwhile, passive funds have enjoyed a surge in popularity: the global ETF industry grew by more than 36 per cent in 2017 to just under $5 trillion.

Chart 1: As markets climb, active managers can underperform

Rebased to year-end 1998. Active US large cap equity funds' performance relative to the market: scores below 1 indicate underperformance. Source: Morningstar, Fidelity International, May 2018.

| Price return, 12 months to: | S&P 500 |

| 30/04/2014 | 17.9% |

| 30/04/2015 | 10.7% |

| 30/04/2016 | -1.0% |

| 30/04/2017 | 15.4% |

| 30/04/2018 | 11.1% |

Source: Thomson Reuters, Fidelity International, May 2018

Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future results.

That said, certain active strategies can still find traction in momentum driven markets. On the face of it, growth-focused managers have a strategic edge, focusing on companies with solid and measurable plans to both capitalise on the buoyant economy, as well as weather any future deterioration in the economic climate. Income and dividend-based strategies can also prove popular, particularly in low interest rate environments. However, blending together a variety of styles across several well-chosen managers is the most sensible tactic to help generate stable returns.

Active strategies also play a pivotal role in constructing a truly diversified portfolio (a factor which pertains throughout a cycle). This is particularly so for less standard asset classes like high yield, emerging market or inflation-linked debt and some non-directional or esoteric strategies, which are often difficult to access passively. High yield, for instance, can be expensive and illiquid, while credit selection is crucial to avoid potential defaulters. Bond index funds are often weighted by the market value of bonds outstanding, so the largest weighting may end up being assigned to the most indebted issuers.

The beginning of the end

Invariably, the good times end and the mid-cycle becomes late-cycle. The turning point isn’t always clear until after the fact; however, it often coincides with central banks raising interest rates to put a lid on overheating inflation. Amid costlier credit, consumers and corporates cut spending and confidence wavers. Macro indicators start to falter or decline and eventually growth decelerates. The economy either limps along for a period, or enters a full-blown recession.

Against this backdrop, markets can head rapidly south: volatility picks up, dispersion creeps higher and asset correlations change - seemingly diversified portfolios can become more correlated. Risk bets are off, while low-beta stocks in defensive sectors such as healthcare, consumer staples and utilities, as well as sovereign debt, begin to look like safer havens. Individual asset selection becomes increasingly crucial too; broad exposure, even to ostensibly non-cyclical segments, is rarely adequate on its own.

While passive index strategies participate in the full upside of rising markets (ex fees), they also suffer all the consequences when markets turn, indeed they embody market risk. It’s in this environment, where pure beta exposure is precarious and investors shift their focus to capital protection, that active managers prove their worth.

A good manager can make a meaningful difference in a downturn. Indiscriminate market sell-offs are inherently inefficient, allowing skilled investors to exploit informational advantages which signal where and when both to take and to avoid exposure. Quality-driven strategies can be particularly beneficial, as companies with solid foundations of consistent and predictable profits, good management and healthy balance sheets become increasingly attractive.

Chart 2: Annual S&P return vs manager outperformance since 2000

Source: Strategas Active vs. Passive Investing, March 2018 via Envestnet, Compendium of Industry Trends, 3 April 2018.

Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future results.

However, passive has its place too, particularly in tactical asset allocation. When a manager seeks to augment a broad, diversified portfolio with short-term exposure to a particular sector or theme, or alternatively wants to reduce exposure for a period, it’s often more cost-effective to do so via index trackers.

Where are we now?

Every cycle has its own idiosyncrasies, which can determine the duration of each stage as well as the variables driving markets. In terms of the current cycle, conditions at the time of writing (June 2018) have certainly shifted since the halcyon days of 2017. Developed markets are sending some late-cycle signals as growth momentum wanes, central banks tighten monetary policy and the climb in oil prices puts further pressure on inflation. Meanwhile, market volatility has picked up from record lows and asset correlations have weakened.

A recession seems unlikely in the short term. However, a more cautious approach to portfolio construction is warranted to stabilise returns and protect capital against a potential, more troubling scenario. It’s probably a good time to reduce overall beta exposure as markets take stock of a cooler economic outlook. Passive strategies are not overly useful on their own when it comes to mitigating risks, given they essentially mimic a broader index: as external conditions become less certain, markets often react accordingly.

As always, diversification is crucial to building a robust portfolio and now seems like a particularly good time to reduce risk in any one single idea. Meanwhile, it would pay to take a more considered, discerning approach to allocation, perhaps including higher-quality, less economically sensitive asset classes and sectors.

.PNG)