Biodiversity loss has become a crucial issue for investors and companies alike. A Brazilian paper and pulp maker recently launched the first ‘transition’ bond with specific rewilding targets, prompting us to talk to another pulp maker about how it is preserving biodiversity and reducing carbon emissions.

Spix’s macaw, the cryptic treehunter and alagoas foliage gleaner birds sound like the product of an active imagination. Unfortunately our imagination is the only place they live on, after being driven to extinction from Brazilian forests - just three of the many species lost since 2000.[1] The devastation caused by human encroachment into natural habitats, exacerbated by climate change, has become a critical issue for investors and is a key theme for Fidelity International in 2021. Paper and pulp production is just one such encroachment, and we recently engaged with a paper and pulp manufacturer, Suzano, on how it is addressing biodiversity and reducing carbon emissions. All this in the wake of the world’s first ‘transition’ bond linked explicitly to rewilding. Our aim was to use the platform we have as fixed income investors to persuade the company to introduce sustainable practices.

Natural capital is at risk

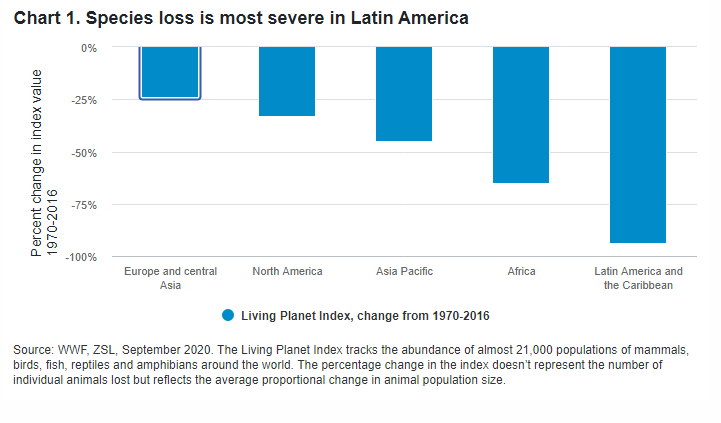

Biodiversity is being lost at an alarming rate around the world, but most severely in Latin America due to deforestation and climate change. The abundance of species in Latin America and the Caribbean has fallen by 94 per cent since 1970 (see chart 1). Unless companies monitor and preserve biodiversity directly, the situation will only get worse.

Paper and pulp companies rely on thirsty, fast-growing species like eucalyptus to create their products at scale. But these monoculture plantations have been criticised by some Non-Governmental Organisations (NGOs) as ‘green deserts’ that threaten the region’s fast diminishing ecosystems. Not all paper companies cut down native forests, but even those with zero-deforestation policies typically replant degraded agricultural land with a single species.

These companies face other big environmental and social challenges. They have to reduce carbon emissions, conserve and recycle the huge amount of water they use, and look after their local communities. This makes it hard to focus solely on biodiversity. For example, the ‘green deserts’ of new, fast-growing trees also act as carbon sinks that reduce emissions. On the other hand, environmental NGOs argue that plantations in fact store less carbon than native forests, meaning shrinking natural capital has an impact on carbon emissions as well.[2]

New rewilding bond plants a seed for broader engagement

Some paper companies, including Suzano, Klabin and UPM, have sought to preserve natural capital. But only a handful have so far tied it to their financing. UPM has linked a revolving credit facility’s margin to both biodiversity and emission targets,[3] while Suzano’s Brazilian counterpart, Klabin, recently became the first company to issue a transition bond with a specific rewilding target, thereby planting a seed for broader engagement on biodiversity. We welcome this development and are extending our engagement to several other paper firms, in addition to Suzano, to encourage similar innovation.

Better disclosure needed

As the world’s largest pulp producer, Suzano was a natural candidate for our first biodiversity-focused engagement with the sector. We were also keen to speak to Suzano because while its emissions-linked bond looked attractive, it had a low MSCI rating and we wanted to find out why. During our call with the company it attributed its low rating to reduced disclosure after it merged with Fibria, another pulp manufacturer. It also pointed to the underlying methodologies of some third-party ratings which it found hard to understand and therefore difficult to improve on.

Suzano believed it could address the issue by telling ratings agencies about its efforts to reduce carbon emissions and to strengthen community relations. It has already worked with CDP (formerly the Carbon Disclosure Project) to improve its disclosure rating and has joined sustainability indices with disclosure requirements.

We agreed with Suzano that the external perception of the company did not reflect its efforts. But we believed there were still areas where we could help, especially by working with the company to implement ESG best practices that should, in time, lift its rating.

Raising carbon ambitions

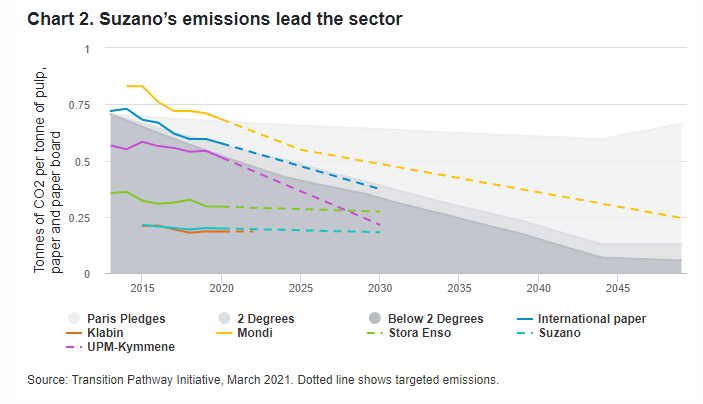

We were especially concerned about whether Suzano’s emissions reduction targets embedded in its bond were ambitious enough.[4] They put it on track to meet the company’s overall goal of reducing carbon emissions by just 15 per cent between 2015 and 2030. Suzano had already achieved 40 per cent of this target by 2020. When we pressed the company on its targets, one of Suzano’s sustainability managers explained that the company is already a low emitter (see chart 2). Even if it took no further action, its emissions would still be consistent with limiting global warming to 2°C above pre-industrial times by 2040. With such low emissions already, Suzano told us it was a case of making marginal improvements.

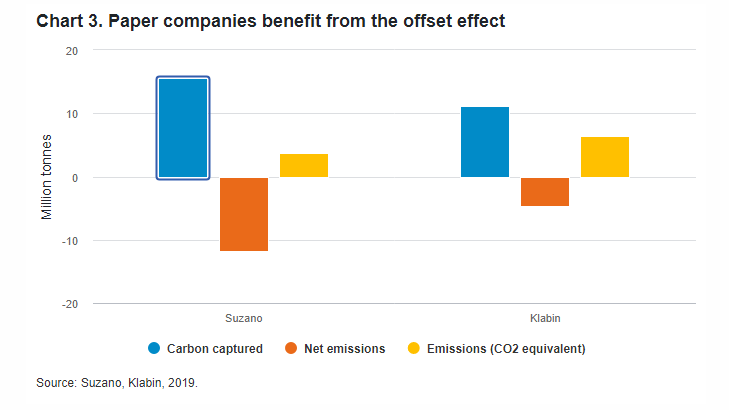

Nonetheless, we encouraged the company to set yet more ambitious emissions reduction goals, moving from a 2°C increase to 1.5°C, validated by the Science Based Targets initiative. Suzano believes the methodology unfairly penalises companies with lower emissions and doesn’t sufficiently account for the carbon offsets that plantations provide. Indeed, the company’s emissions are more than cancelled out by the carbon captured in its plantations (see chart 3). But, in our view, offsets are only part of the net zero story and no substitute for real cuts in global emissions.

A thornier issue

Biodiversity appears to be a thornier issue. Natural capital was conspicuously absent from Suzano’s 2020 sustainability targets. When we asked why, Suzano told us that it would soon release a biodiversity target that it had been working on for some time and had budgeted for. But it said the target was more complicated than those for carbon emissions and water, due to the need to cooperate with neighbouring plantations, communities, and academics and to take a full “landscape” approach that ensures everyone works together to protect species and regenerate forests. The company said the target would be unveiled in Q2 2021.

Suzano explained it had already taken measures to preserve species in the Amazon rainforest, the Atlantic forest along the Brazilian coast and the Cerrado savanna in the centre of the country. This includes interspersing its plantations with actively restored native forest and growing trees of different ages to manage water use. Restoration is particularly important in the Atlantic forest, which is only 13 per cent of its original size.

The company also has a zero-deforestation policy throughout its supply chain. There are 100 million hectares of degraded pastureland in Brazil and planting eucalyptus in these areas helps preserve biodiversity by creating food and shelter for animals, albeit less than native forests provide.

Measuring biodiversity success

We asked Suzano how it measures success when it comes to biodiversity. Suzano’s sustainability manager told us that about 80 per cent of the firm’s land is certified by the Forestry Stewardship Council (FSC) and that continued certification depends upon there being no human rights or biodiversity violations. Suzano also monitors 2,700[5] plants and animals on its land so that it can track any new and endangered species.

As Suzano grows more eucalyptus, it said it will aim to keep the share of preserved forest stable at about 40 per cent. Suzano told us that the rich biodiversity in these areas protects the surrounding eucalyptus trees from disease, but it is not clear whether this percentage is enough to prevent further species loss and is something we intend to explore further.

We also queried whether chemicals used to control the plantations ever spill over into the native forest or if the trucks transporting harvested eucalyptus cross the preserved areas. Suzano told us it considers this when planning roads and harvests towards the native forest, giving animals time to seek shelter. It has also reduced its use of agricultural chemicals. Suzano does seem aware that its harvesting activities could affect animal habitats but we are still unsure whether it is doing enough to mitigate any negative side effects.

Work in progress

We have generally been impressed by Suzano’s sustainability team, its intentions and its receptiveness to our suggestions. We continue to encourage the company to be bolder on carbon emissions and to set an ambitious biodiversity target, both of which should help it improve its external ESG ratings over time. We have already raised the rating we award Suzano in our own assessment. Many emerging market issuers have only just started disclosing sustainability metrics and look to us for advice on how they can improve their external ESG ratings. Launching transition bonds with concrete, measurable targets that aim to reduce carbon emissions and preserve our common natural capital are increasingly a way in which companies can seek to arrest catastrophic species loss, boost their ESG credentials and attract investor capital.

[1] Eight bird species are first confirmed avian extinctions this decade, The Guardian, September 2018.

[2] Roll up, roll up! The Net Zero Circus is coming to a forest near you, Global Forest Coalition, September 2020.

[3] UPM signs a EUR 750 million revolving credit facility with a margin tied to long-term biodiversity and climate targets, UPM.com, March 2020.

[4] Suzano sustainability-linked securities framework, September 2020.

[5] Environment, Suzano.com