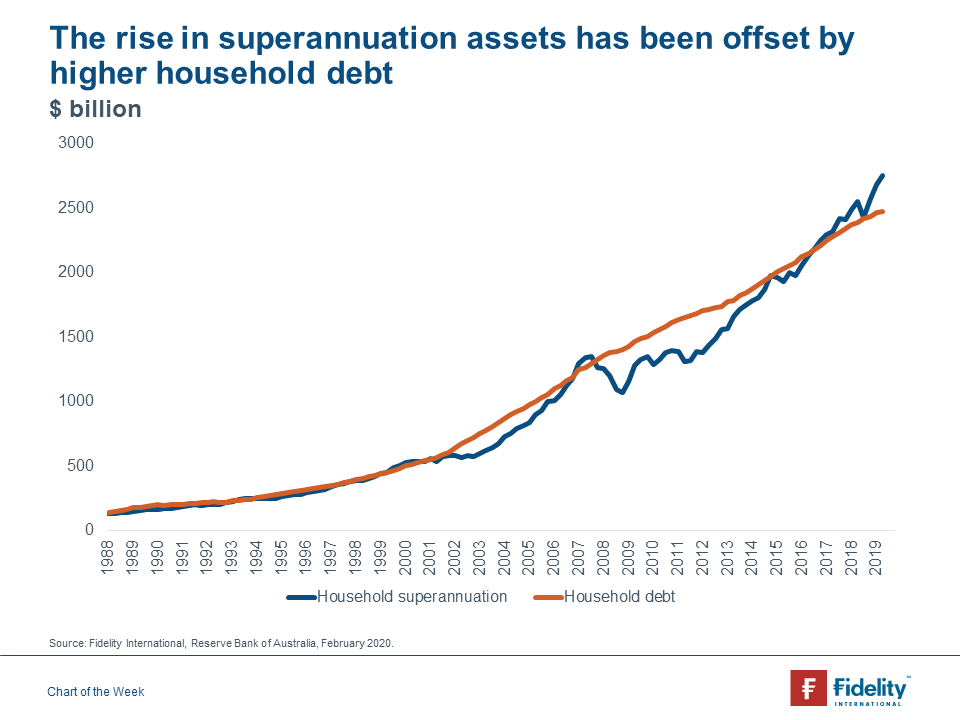

Australians have been making compulsory superannuation contributions since 1992. Today, there is around $2.75 trillion dollars in retirement savings in superannuation funds. As a result of the accumulation and growth of this savings pool, Australia now has the fourth-largest pension market in the world. On the other side of the balance sheet, Australians also have the second-highest level of household debt to GDP in the world at around 120 per cent of GDP. Household debt has grown in nominal terms from $217 billion dollars in June 1992 to almost $2.5 trillion dollars today.

Total superannuation assets and household debt have grown at a similar rate since 1992, suggesting that the superannuation saved by Australians has largely been offset by increased borrowing. It appears that the knowledge that most Australians have a pool of money waiting for them in retirement has resulted in the Australians becoming more comfortable with accumulating higher levels of debt during their working lives. Lower interest rates, increases in household incomes, and higher house prices have also contributed to the run-up in debt seen over the past 27 years.

Looking forward, the RBA’s three interest rate cuts have enabled Australia’s property market to stage a remarkable turnaround. After falling 10% from October 2017, house prices are now only 3% from being back at a record. It shows that monetary policy still works in Australia. Ultimately lower interest rates are intended to encourage businesses and households to borrow.

Higher house prices mean that Australians, in general, will be required to accumulate more debt should they seek to buy a property. This is being confirmed by housing finance data showing that the value of owner-occupier housing loan approvals is 20.5% higher than the trough in May 2019. Whilst higher house prices will likely stimulate the economy in the short-run as households feel wealthier and spend, higher debt may prove to become a headache for the RBA in the longer-run, as households typically react to a negative shock (like a loss of income or rising interest rates) by cutting spending sharply in order to maintain their mortgage payments.