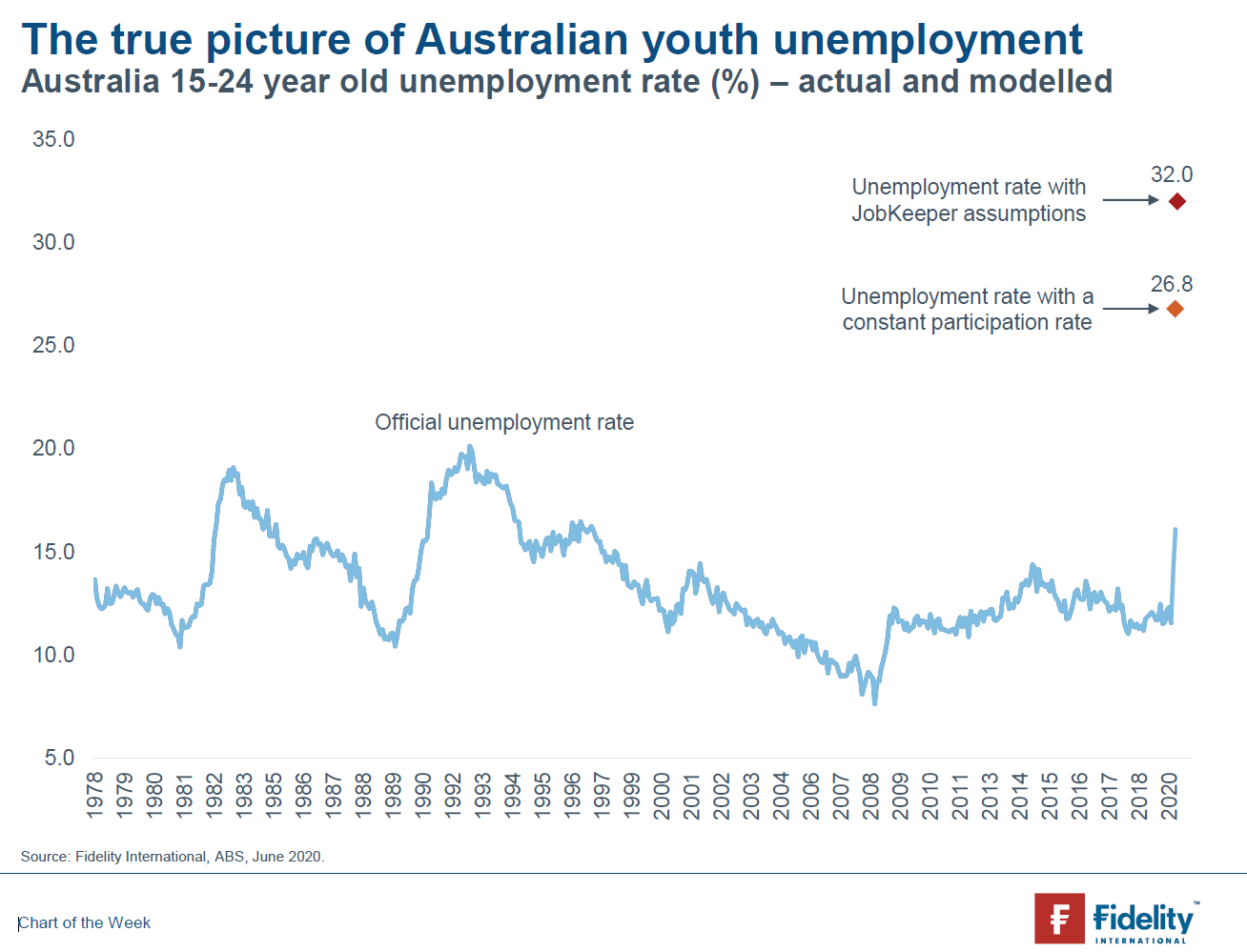

According to the latest unemployment statistics, over 300,000 Australians aged between 15-24 are now unemployed and over 280,000 dropped out of the labour force in April and May. This has been reflected in a rising youth unemployment rate, which rose from 11.6% in March to 16.1% in May. Arguably, the unemployment rate is not reflecting the true devastation that COVID-19 has had on Australia’s 15-24 year old workforce, given a large proportion are employed in the heavily impacted food service, retail, hospitality, and tourism sectors. Over 3.3 million Australians are on JobKeeper payments with many coming from these key affected sectors. These Australians are not recorded as unemployed, but many are likely to be aged between 15-24, and are uncertain as to whether they will remain employed if or when the JobKeeper payments cease.

The current crisis is likely to have long-lasting impacts for Australia’s youth workforce. Academic studies in the US have shown that being unemployed while you are young has long-term implications for future earnings. These earnings losses appear to be the result of lost work experience, falling labour market skills, relatively lower perceptions of labour market worth, and the negative connotations that unemployment has with employers. There are also severe social ramifications, including loss of motivation and erosion of confidence. Globally, high youth unemployment levels have also been associated with social unrest, higher levels of criminal activity and political turmoil.

To attempt to gain a true picture of the impact of COVID-19 lockdown measures on Australia’s youth workforce, we can calculate an unemployment rate based on the assumption that those who dropped out of the labour force in April and May continued to look for a job. Under this assumption, these people are counted as unemployed. Under this assumption, Australia’s youth unemployment rate is currently 26.8%, rather than the official figure of 16.1% for May. Taking the analysis one step further, those aged 15-24 make up around 15% of the labour force. Assuming this age cohort represents an equivalent proportion of the 3.3 million people that are currently receiving the JobKeeper payment, and 25% of those on JobKeeper lose their job when the entitlement ends, then the youth unemployment rate rises to 32%. Arguably, this underestimates the true level of youth unemployment, as this age cohort likely represents a greater proportion of those receiving JobKeeper payments.

For policymakers, the question becomes how to support the youth of Australia during this recessionary period. In this sense, we may be able to learn a lesson from the 1930s during the Great Depression. According to Collin O’Mara, president and CEO of the National Wildlife Federation, in 1933 President Franklin Roosevelt created the Civilian Conservation Corps. The C.C.C. hired young unemployed men for projects in forestry, soil conservation and recreation. By 1942, 3.4 million participants had planted more than three billion trees, built hundreds of parks and wildlife refuges and completed thousands of miles of trails and roads. The C.C.C. was the most expansive and successful youth employment program in American history.

At this unprecedented time, innovative programs - like the C.C.C. in the 1930s - may offer current policymakers some ideas for the types of policies required to support younger generations of Australians.