China is bucking the US-led trend towards higher interest rates, and the resulting yield divergence has huge implications for fixed-income investors and currency markets globally.

While inflation is forcing some of the world to raise headline interest rates, China is dancing to a different tune and retains room for further easing. The People’s Bank of China unexpectedly cut interest rates for the third time this year in late August, as growth continued to slow amid a property downturn, consumption weakness and Covid lockdowns. Softening exports due to weaker overseas demand also weighed on the economic outlook.

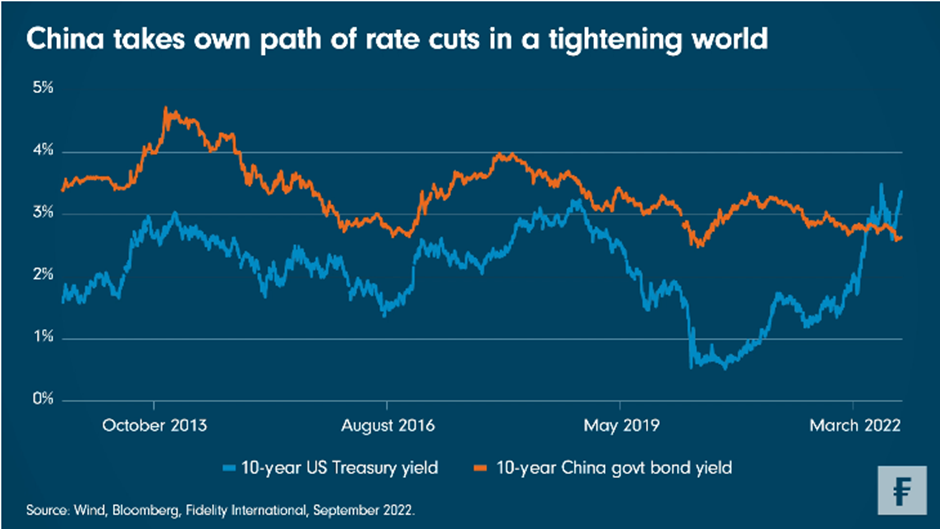

Reviving growth has become a top priority, and Chinese policymakers, unlike their US and European counterparts, are blessed with domestic inflation that’s staying below 3 percent. In the second quarter, China’s benchmark 10-year government bond yield dipped below the 10-year Treasury yield for the first time in more than a decade. Since that crossing of paths, the yield gap has widened to more than 60 basis points. On the face of it this would seem to diminish the relative appeal for global investors of holding onshore China sovereign debt, although the picture is more nuanced once real yields after adjusting for inflation are taken into account, and set against the broader macroeconomic backdrop.

To this end, we see a high chance of additional rate cuts in China in the near future, which will offer support for Chinese onshore bonds but also add to pressure for the renminbi to weaken further against the dollar. China’s easing measures so far this year have done little to boost corporate borrowing or revive business activity, building the case for more and stronger policy action. That said, we don’t expect to see anything like the dramatic levels of monetary or fiscal intervention that major developed market policymakers undertook in the wake of their Covid-induced economic slowdowns.

The US and the European economies are on a very different trajectory from China’s. Soaring energy prices, rising labour costs and large coronavirus stimulus have left the US economy overheated and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has pushed Europe’s inflation to a record high. US and euro-zone inflation rates were 8.5 percent and 8.9 percent respectively in July, while the CPI index in China was only 2.7 percent in the same month. New data announced this September showed inflation again topped estimates in the US in August and triggered a selloff in markets.

China’s cycle of rate cuts and the soft economic outlook may cause the Chinese currency to weaken further against the dollar. Even so, capital outflows do not appear to be a big concern for China’s central bank because of the nation’s controls on cross-border flows, which are bolstered by the country’s US$3 trillion in foreign currency reserves.

Over the long run, we see demographic trends adding downward pressure to China’s neutral interest rate for decades to come, as the population ages. This dynamic typically leads to lower productivity, lower return on capital and therefore lower rates. This suggests yield divergence has scope to widen further over the very long term. But in the short term, all eyes are on the next rate calls, and the direction of those couldn’t be clearer.