The quantitative tightening of US financial conditions will inevitably strain parts of the banking system. But it seems this time the US Federal Reserve (Fed) has the tools it needs to avoid a widespread near-term squeeze.

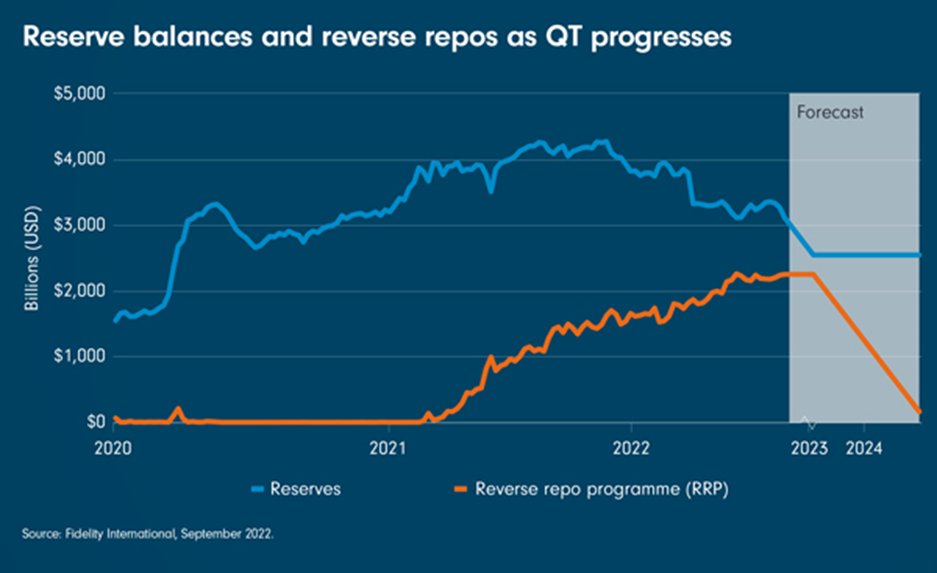

Since the start of the year, banks have been shedding excess reserves built on the back of the Fed's quantitative easing (QE) program. At the same time balances in the separate reverse repo program (RRP) have continued to grow. As the Fed has moved from easing to tightening, the fall-off in reserves has accelerated rapidly, with total banking reserves declining to US$3.1tn today from US$4tn at the start of the year.

Against this backdrop, some have begun to question whether the Fed will have to end its quantitative tightening (QT) programme early. We think this is unlikely and that QT should be able to continue for an extended period. But in the near term, QT will probably begin to exert upward pressure on rates in short-term funding markets.

The Fed aims to operate a system with ample reserves balances, one that maintains a decent buffer above what banks consider their least comfortable level of reserves (LCLOR). In the previous tightening cycle of 2015-2018, Fed survey data estimated the LCLOR at around US$1tn. However, in September 2019, with reserves at US$1.4tn, a sudden and acute shortage of liquidity saw repo levels jump 3.05 per cent over two days. In response, the Fed started a series of emergency repo operations to supply liquidity to the market.

In the face of QT, could money markets face a similar squeeze today? At present, the LCLOR is estimated to be considerably higher than in 2019 with suggestions of around US$2tn, so with a buffer it is likely that banks could continue to shed reserves without pressure until we approach the US$2.5tn level, or around US$600bn lower than present. This could happen as soon as February next year - assuming that QT continues at the new cap of $95bn a month, and also that reserves continue to fall while the RRP stays steady. But what would that mean for markets?

When QT takes hold

When banks are over-reserved (as they are at present), it puts pressure on both their leverage ratios and their Global Systemically Important Banks (GSIB) scores. For this reason, they have so far been happy to let reserves fall and not compete for funding in wholesale markets. But as reserves continue to drain and we get towards the buffer levels banks are comfortable with, they will have to start competing for funding in the market. This will in turn raise funding rates in short-term markets, leading to higher repo and Fed Funds rates, wider Libor-OIS spreads (an indication of short-term credit risk) and a rise in the cross-currency basis (another measure of the shortage, or surplus, of dollars in the market). This will be the point at which reserves will stabilise and balances in the reverse repo program begin to fall from their current levels of around US$2.2tn. Overall, this is when QT starts to have the maximum effect in tightening financial conditions.

It is possible that RRP balances may prove stickier than anticipated, leading to a continued drain of reserves that in turn puts elevated pressure on funding markets. Will that cause the kind of spike in rates we saw in 2019? We believe it is unlikely. The Fed now has an alternative standing repo facility as a backstop so banks will be able to maintain reserves at desired levels.

Overall, with potentially a further US$600bn of reserves and US$2.2tn of RRP balances to drain, we think QT can continue through 2024. This will result in greater competition in funding markets and higher short-term rates and spreads going forward. But it won’t happen overnight.