China’s onshore gold price premium has expanded, spurring cross-border arbitrage and sucking investment away from other assets. But the latest gold rush also acts as a contrarian indicator for the broader economy, implying stronger policy measures are called for to shore up consumer confidence and put the shine back into China’s markets.

As the old Chinese saying goes, “hoard gold in troubled times, and hoard jade in boom eras.” The yellow metal is prized for maintaining its value and being readily portable during turbulent times, while jade products tend to represent higher artistic value and more subjective (or speculative) pricing.

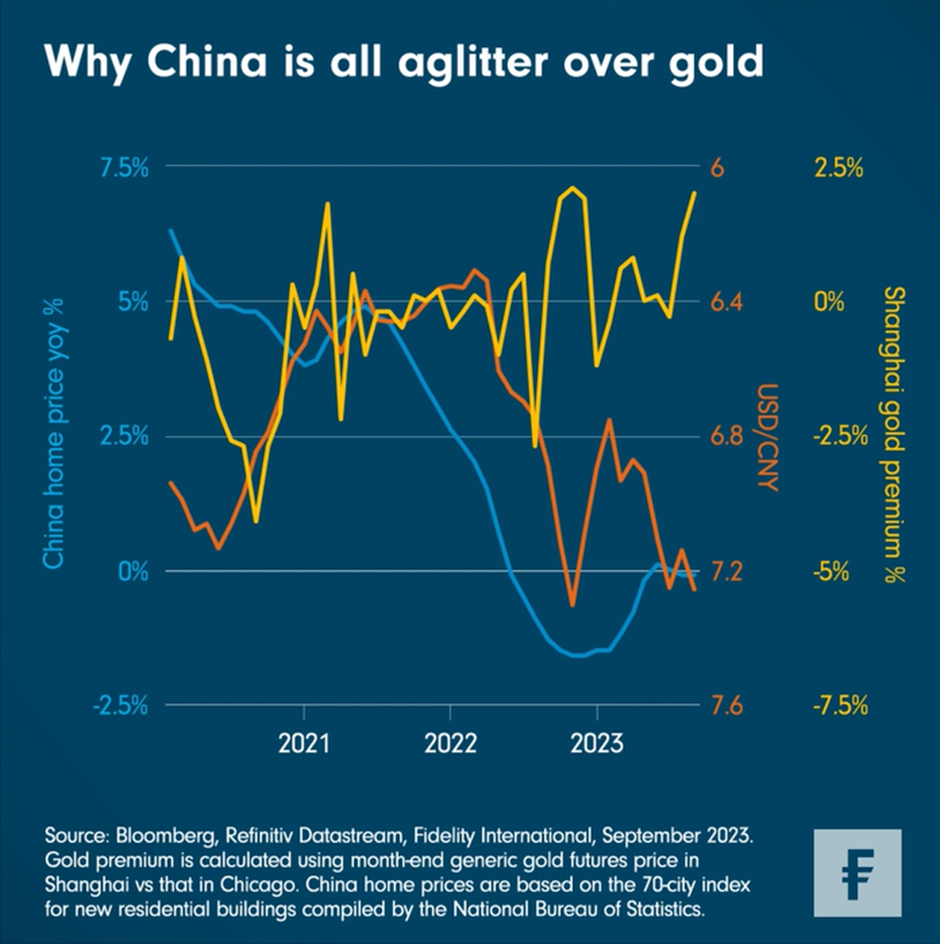

That may help to explain the rush for gold that’s gripped China’s onshore commodities futures market in recent weeks, even while a confluence of concerns has depressed everything from the renminbi’s exchange rate to Chinese equity valuations and housing prices. This week’s Chart Room takes a closer look at the price gap between onshore and offshore gold futures as compared to the housing and foreign exchange markets.

With the renminbi trading near 16-year lows versus the dollar, Chinese investors are scrambling for practical hedges against further depreciation.

Residential property traditionally provides this diversification benefit, but the prolonged downturn in home prices has weakened its appeal. Meanwhile the onshore stock market has ranked among the world’s worst performers so far this year, leaving equities undesirable to many people (except perhaps those looking for value or seeking contrarian buy signals). Strict capital controls mean many overseas asset markets are difficult to access for mainland residents.

That leaves China’s onshore gold market as one of the easiest options. The onshore China price premium for the metal, or the difference between dollar-denominated generic futures prices in Shanghai and the US, has implied room for arbitrage. Local media reports describe a recent trend of people buying gold in Hong Kong, where prices are more in line with global markets, and reselling it in the neighbouring mainland city of Shenzhen for a quick profit.

It’s not just futures markets that have been set aglitter. Although heightened gold demand doesn’t bode well for consumption in China or the overall economy, it does tend to benefit segments such as jewellery retailers and gold miners. In August, nationwide jewellery sales jumped 33 per cent from the same month of 2019, while many other consumer segments are still struggling to regain pre-Covid levels.

It won’t last forever, and we expect the premiums will revert to their mean, but what about after the gold rush? Much of what happens will depend on policy measures to stabilise the property market, create more jobs, and, most importantly, to bolster consumer confidence. As former Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao put it during the 2008-09 global financial crisis, “Confidence is the most important thing, more important than gold or currency.”