At the turn of the year, we ask our analysts how companies see the year ahead, and how they are positioning their businesses for what they think is coming. Our analysts see cost and wage pressures building over the next 12 months but do not expect companies to respond by raising prices significantly, partly because of healthy margin buffers.

Signs of cost and wage inflation creeping up

This year almost two thirds of our analysts see higher input costs, up from half last year. Expectations of increased costs in industrials, energy and materials are classic indicators the global economy is now late in the economic cycle.

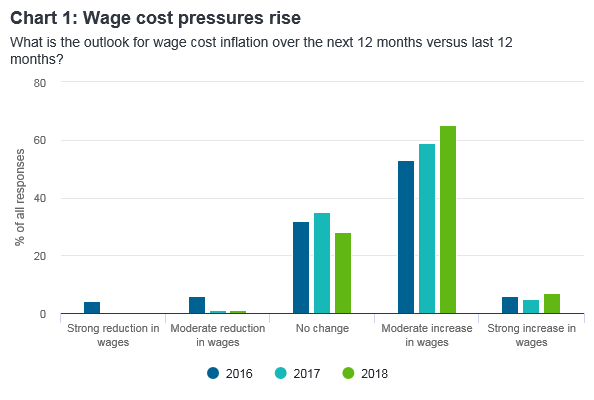

A majority of analysts (72 per cent) also expect an increase in wages over the next 12 months, compared to 64 per cent last year, led by China, Europe and the US. Almost all of these analysts, however, expect the increase to be moderate, except in the EMEA/Latin America region, where third of analysts expect ‘strong’ wage increases.

US President Donald Trump’s tax reforms may add to wage inflationary pressures as companies are expected to pass on some of the benefit of tax cuts to their employees.

Source: Fidelity Analyst Survey 2018

Output price momentum harder to find

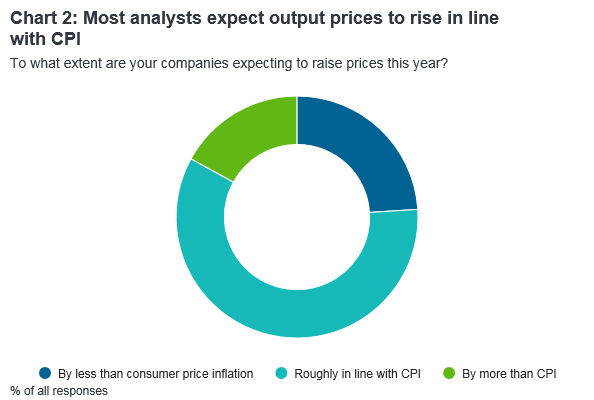

Despite rising costs, the vast majority of analysts say their companies’ price hikes will not exceed inflation. Six out of ten analysts across sectors see output prices rising in line with consumer price inflation (CPI), except in telecoms where most analysts expect prices to rise by less than CPI.

With margins in many sectors at near-record highs, companies are well placed to absorb some cost inflation. This helps to explain why fewer than one in five analysts say their companies are likely to raise their prices by more than CPI. Most of these are in materials and energy - not entirely surprising as these are the two sectors where cost price inflation is most pervasive, according to our survey.

Source: Fidelity Analyst Survey 2018

Pricing power is growing

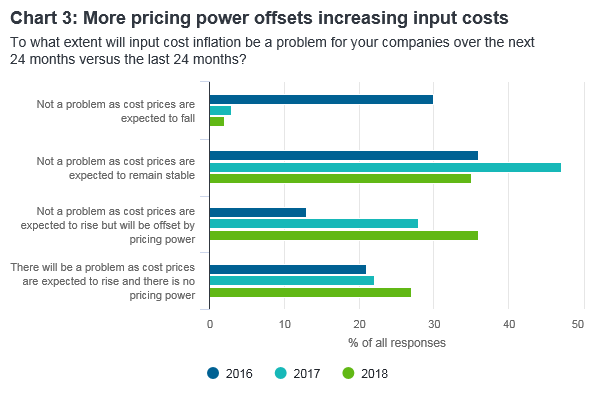

Even if most companies look set to show restraint when it comes to raising prices, more companies are in a position to pass rising input costs on to their clients. This is the case across most sectors, especially in consumer staples, energy and materials.

Consumer discretionary and industrials companies, however, appear to have less of a buffer against rising costs.

Rising inflation would leave financials and materials companies most likely to boost margins. Industrials firms may be less fortunate according to our analysts; given their relative lack of pricing power, higher inflation would most likely lead to margin compression and end the sector’s two-decade run of steady margin gains.

Despite expectations of inflation finally edging up, deflationary factors such as improvements in technology, globalisation and outsourcing are still a force and are expected to keep inflation in check.

Our China analysts, for example, emphasise that growing wage costs are fuelling rapid automation and technological innovation across both ‘old’ and ‘new’ economy sectors, as companies fear they might otherwise lose their global competitive edge.

The lure of lower costs also means that companies are still seeking out cheaper manufacturing opportunities, suggesting that the outsourcing story still has legs.

Source: Fidelity Analyst Survey 2018.

Wage rises in a globalised world can hit profits: a tale of two continents

Wage inflation in the US is finally showing signs of revival. This might not seem so relevant for a Zurich-based baker, but in today’s globalised value chains, wage increases in one part of the world can swiftly trigger higher costs for businesses located in another.

Aryzta, the food business baker that prides itself on its speciality baking, recently issued a profit warning citing higher distribution and labour costs for its underperforming US business. (Aryzta is one of the world’s largest bakery companies and makes hamburger buns for McDonalds.)

“The trucking sector in the US is very tight, exacerbated by a shortage of drivers and trucks,” explains Christopher Moore, director of research. “There are new regulations: you now have to pass drink and drugs tests if you are a US driver, and hours of service are now being electronically logged and enforced to ensure compliance. And it’s a very unhealthy profession - you’re cooped up in a cab most days so driver turnover tends to run at very high levels. This shortage of drivers means wage demands are quite high.

“The swift rebound in the US from the mini industrial recession of 2014-2015, which has caught some people by surprise, has made these pressures more acute, and given rise to bottlenecks in sectors that rely on trucking. Because it takes time for the supply of both truckers and trucks to catch up, the prices for trucking journeys and truckers’ wages are rising, in many cases at double digit rates. That’s great for the trucking industry, but anyone using their services has to absorb an additional input cost.

“If you’ve got pricing power yourself - if your margins are 30 per cent or so - then a small erosion of your margin in the order of one or two per cent wouldn’t matter much. But if you are on wafer-thin margins, like many food businesses, even a relatively modest increase in costs can pose a real risk to your business, as we have seen in Aryzta’s case.

“We may see similar problems with other low-margin companies. Typically, distribution will make up a high proportion of their costs so rising distribution prices can really damage their business.”