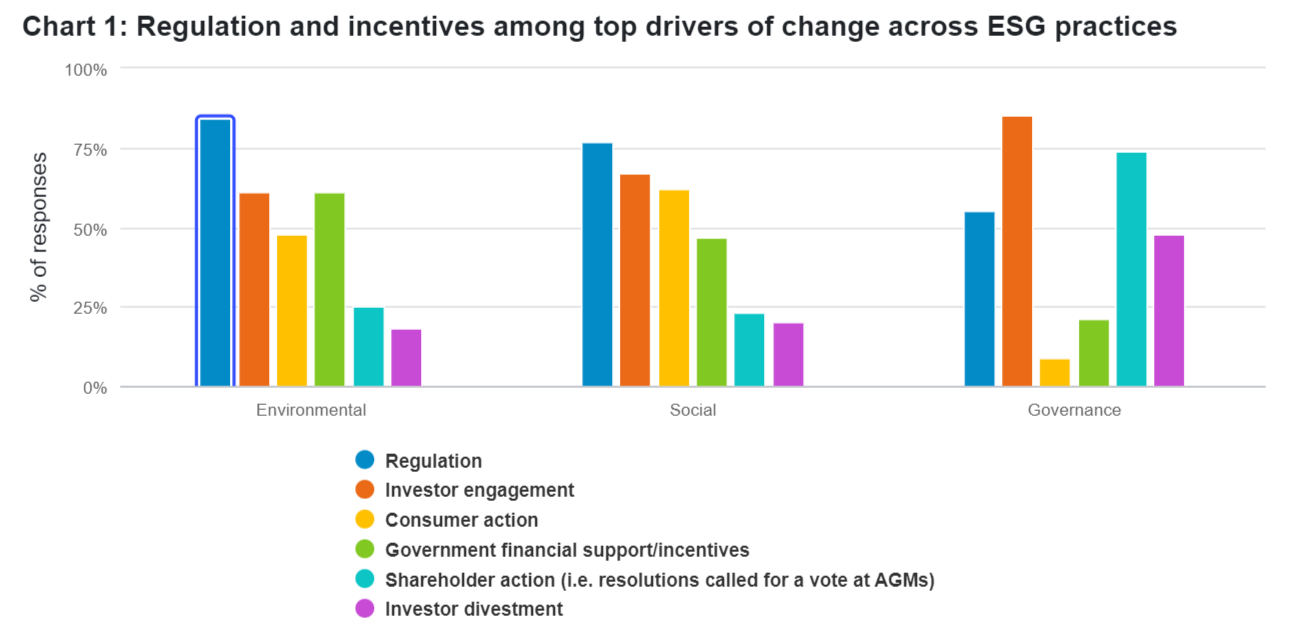

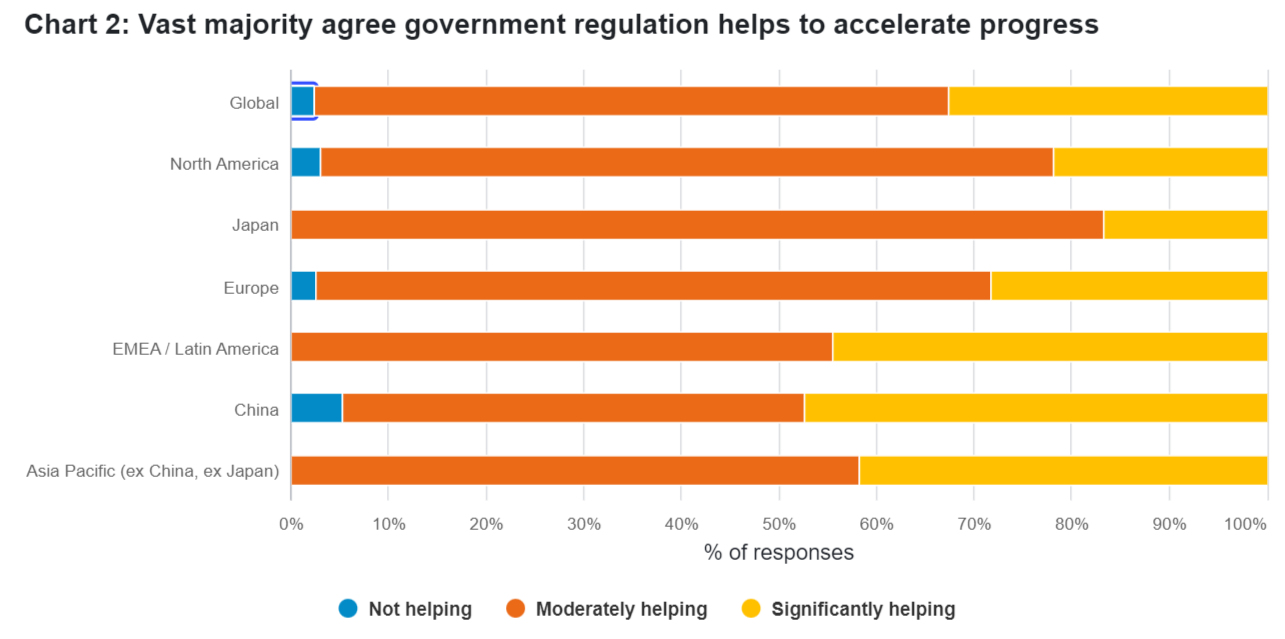

One of the strongest messages communicated by our analysts in this year’s ESG Analyst Survey is the effectiveness of government regulation in changing companies’ behaviour. While investors, consumers, employees, and competitors all have a role to play in shifting practices, it is only the introduction of enforceable legislation and regulation that can require businesses to change.

The three years over which we have run the ESG Survey have been some of the strangest and most difficult we’ve seen across the financial markets. Beginning in 2021 when much of the world was still locked down, our analysts followed their sectors through a war in Europe, supply chain crises, and rising inflation. And despite these existential challenges, they have tracked tangible and heartening improvements in companies’ ESG profiles.

But it is clear from this year’s survey that the looming threat of a recession has now slowed progress and that the financing necessary for companies to meet their net zero goals is seriously lacking. The survey does offer insights from Fidelity’s analysts as to how this gap can be overcome, however.

This dynamic is particularly noticeable in China, where the government’s pledge to make the country carbon neutral by 2060 has shown the power of top-down intervention.

Where next?

Our analysts have identified a range of both push and pull policies that they think will encourage companies improve their practices. Tristan Purcell, an equity research analyst focusing on European industrials, recognises that more stringent building regulation and the faster enforced adoption of renewables in power generation have been effective methods for driving change, for example.

Harriet Wildgoose, an analyst in our sustainable investing team, notes that in agriculture and across food systems – segments that generate around a third of our greenhouse gas emissions1 – current incentives are “often misaligned with net zero and nature goals and need to be redirected at the national and regional level towards solutions such as regenerative farming techniques."

Other suggestions from our analysts across industries range eclectically from enforcing the recycling of mattresses to offering rebates on the installation of heat pumps.

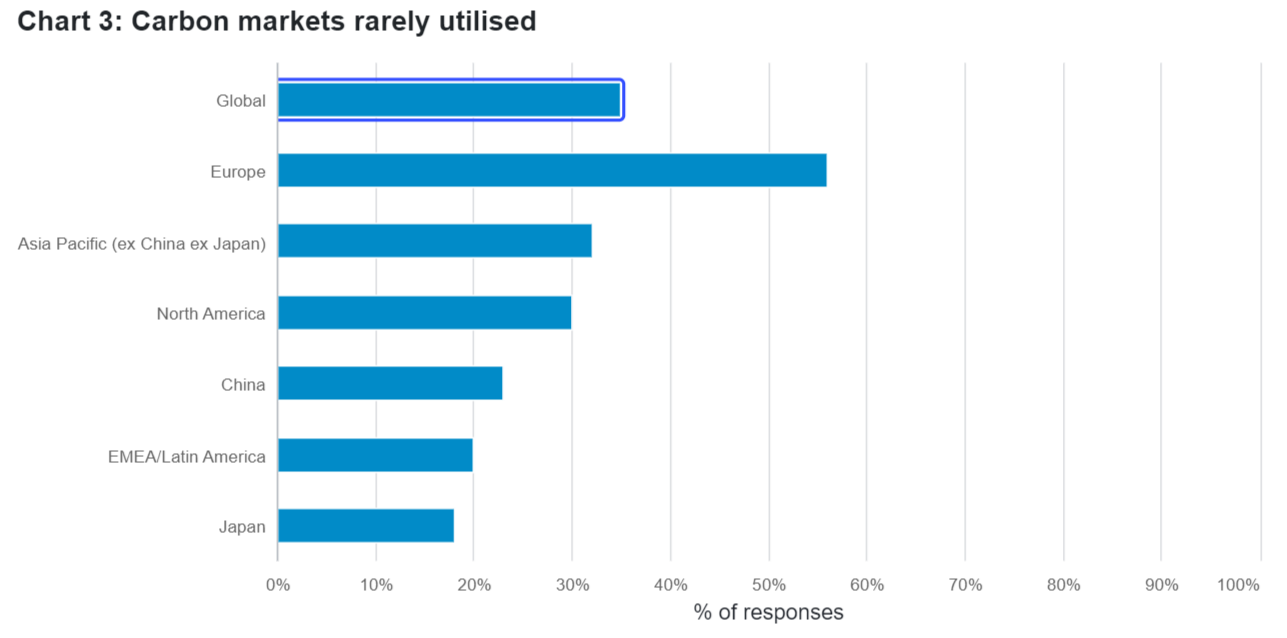

One common theme that emerges is that the alignment of enforceable and legislated regulations across different jurisdictions is critical, with repeated calls from our analysts for carbon to be priced effectively. Pricing in carbon markets is inefficient: companies are able to tap into artificially cheap sources that do not necessarily offset their emissions, and there is little standardisation in the way the market operates across different regions.

Currently, only around a quarter of companies in Fidelity’s coverage use carbon markets as part of their net zero plans.

Taking the measure of things

Sometimes, the most effective regulation can be as simple as requiring companies to measure (and report on) relevant criteria. A cruise line operator I once covered as an analyst didn’t measure anything, whether their ships’ carbon emissions or something as seemingly trivial as how many plastics straws they were using. But the moment they started tracking their performance it triggered changes in their practices and an immediate reduction in the waste they generated.

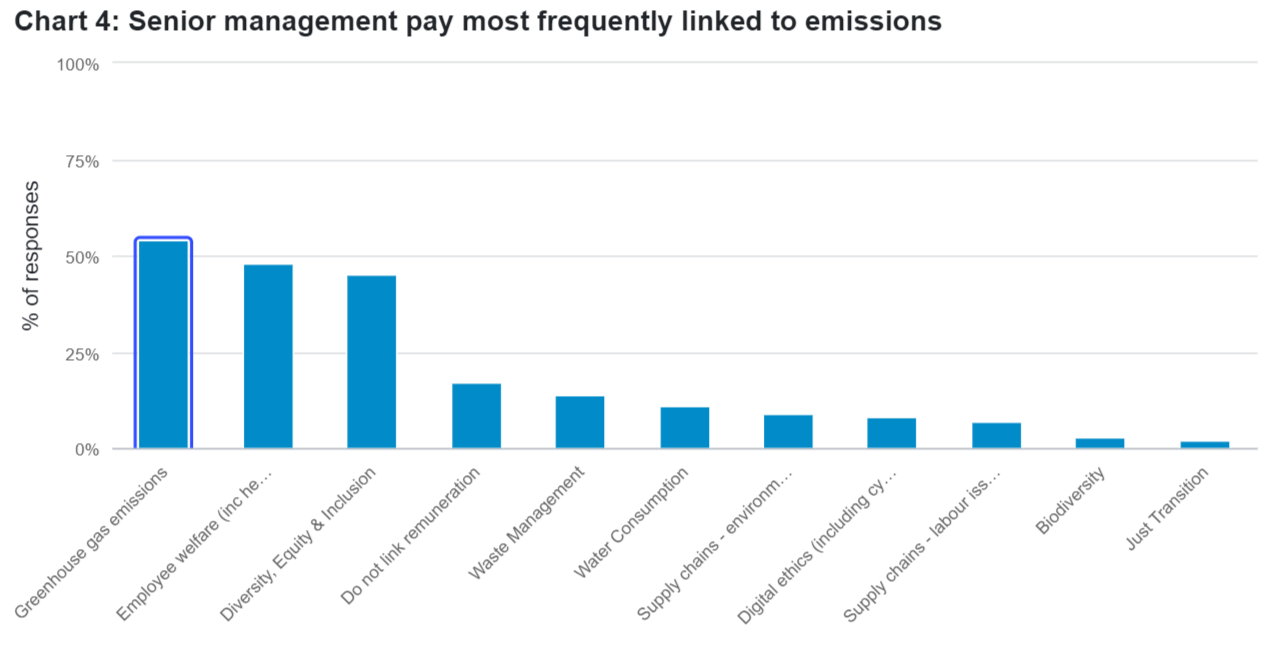

Similarly, since companies have had to report their greenhouse gas emissions they have pushed hard to cut those figures. Even more powerful, perhaps, is that this is now one of the most common sustainability metric linked to senior management teams’ remuneration. Similar regulation insisting that firms measure and disclose diversity and inclusion data means that this has also become a popular metric on which to base compensation.

In contrast, on an issue such as biodiversity there are far fewer required standards for companies to adhere to. As a result, there is a lag in the development of reliable metrics, fewer companies measure their activity, and fewer still pin senior managers’ pay to biodiversity targets. Given progress has been so slow around biodiversity, the potential gains from simple regulatory changes in this area could be remarkable.

Getting engaged

While regulation is essential, the financial world also has an important role to play. A majority of our analysts report that investor engagement and shareholder action are among the most effective ways of encouraging change in governance, and around half place engagement as one of the top three ways to improve environmental and social practices.

Certainly, there have been many instances where Fidelity’s intervention had encouraged specific and meaningful change, such as with the collaborative engagement we led with mining conglomerate Grupo Mexico and the subsequent publication of new emissions targets including a net zero goal for 2050.

Other approaches to encourage the corporate world to a more sustainable future include more intangible elements that are harder to measure such as companies’ willingness to benchmark with global peers, a desire to attract employees, or social or client pressures, all of which can trigger big improvements on their own.

Footnote 1: Food systems are responsible for a third of global anthropogenic GHG emissions, NatureFood, March 2021