Rewind the clock eighteen months to the end of 2022. Equity markets were down around 20% over the preceding 12 months (though the drawdowns from peak to trough were much larger), and all the fears were around a US recession.

In March 2023, US Federal Reserve economists were expecting ‘a mild recession starting later this year’1, while Bloomberg termed it ‘The Most-Anticipated Downturn Ever’2. That was certainly top of the list of fears in my mind too, at the time. Yet, the recession didn’t eventuate, and we have witnessed a sharp rally in world equity markets.

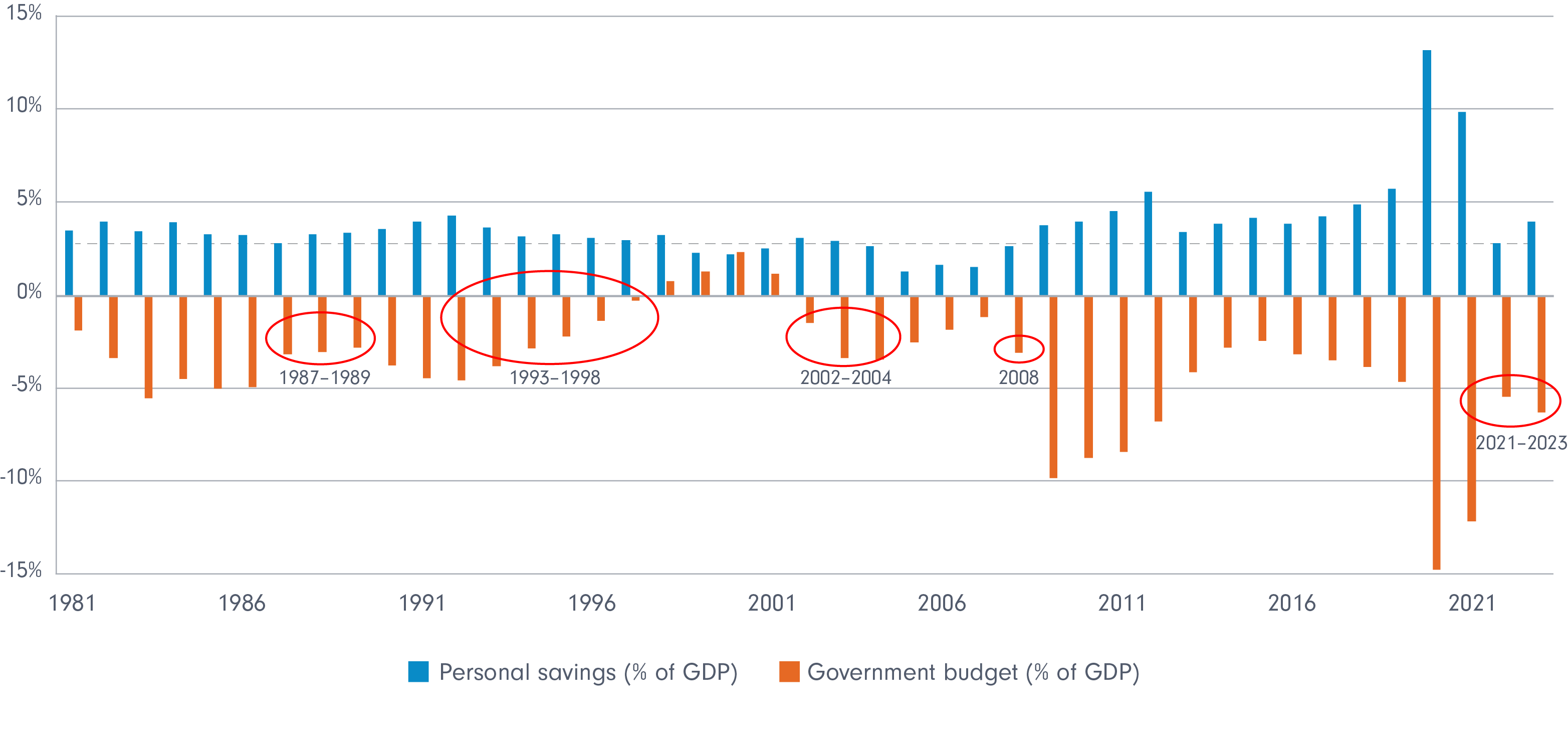

What happened? What sheltered the US economy was an unusual confluence of circumstances, piloted by both the private and public sectors. Chart 1 shows the US fiscal budget deficits and the personal savings rates (both standardised as a percentage of GDP).

Chart 1: Government budget & personal savings

Source: FactSet, FIL

The positive blue bars represent personal savings rates, while the predominantly negative orange bars represent fiscal budget deficits. A few things stand out, including the fact that around the turn of the Millennium, the US did manage a few consecutive years of small budget surpluses.

If we focus on personal savings’, we see huge spikes in 2020 and 2021, driven by the Covid lockdowns. People couldn’t spend on dining, travel or experiences. At the same time, most people remained employed and those who didn’t, received stimulus payments. As a result, most consumers accumulated more savings.

However, as restrictions eased in 2022, consumer behaviour returned to normal, and the savings rates collapsed to more typical low single digit levels. The dotted horizontal line represents the level achieved in 2022, allowing us to easily look at similar periods in the past.

What is notable is that when personal savings rates were at similarly low levels, government budget deficits were also small, highlighted by the circled orange bars. Said differently, when personal savings rates have been small, otherwise expressed as high personal consumption rates, the government hasn’t stimulated the economy because the private sector was doing a good enough job.

What makes the last period unique is that fiscal budget deficits were running at levels previously only associated with high personal savings rates, such as the post-GFC recovery period. Private consumption and spending accelerated in 2022 (some have referred to this as ‘revenge spending’), but budget deficits remained relatively large, meaning that both the private and public sectors were stimulating the US economy at the same time.

These twin forces have been more than enough to offset the increase in interest rates. Many US homeowners and corporates also locked in ultra-low fixed term interest rates during 2020-21, which means that higher interest rates haven’t yet dented spending across the board.

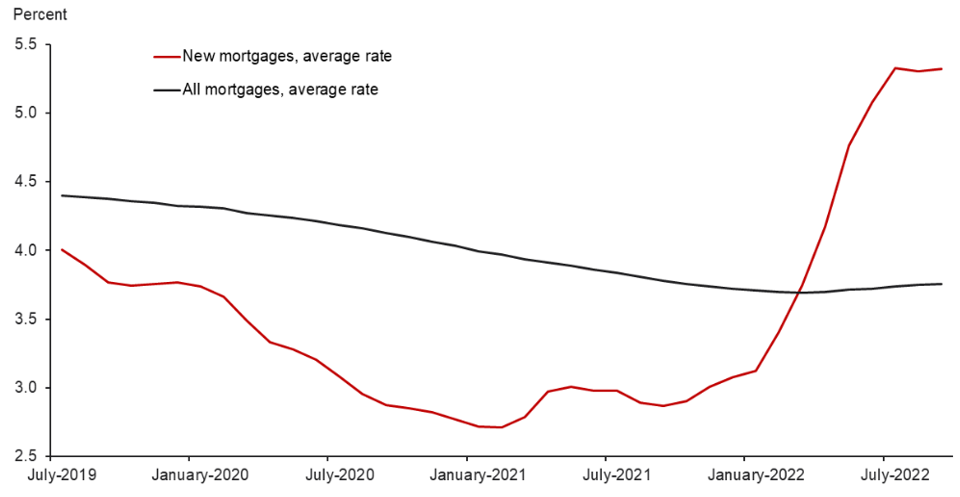

Analysis by the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas3 shows that the average mortgage rate on outstanding debt in the US towards the end of 2022 was around 4%, despite rates on new mortgages at the time averaging 5.5%.

Chart 2: Average outstanding mortgage rate remains very low

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas

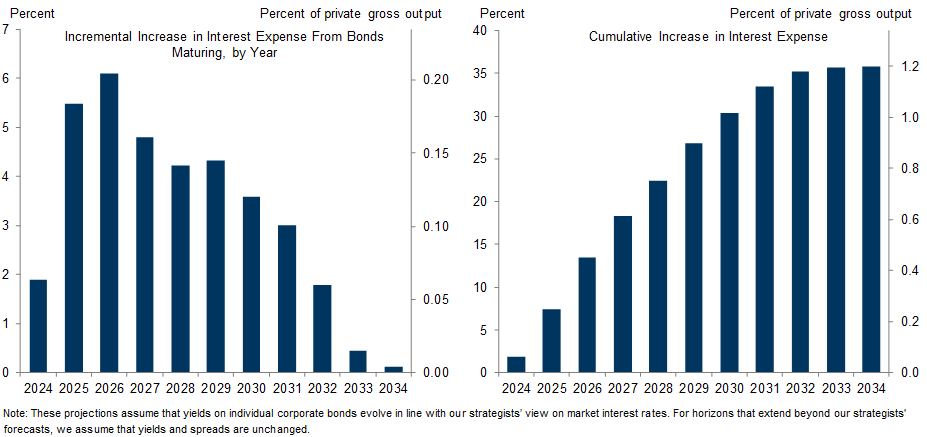

Similarly, based on estimates by Goldman Sachs, corporate interest expense won’t rise in a material way until around 2025-20264.

Chart 3: We estimate that refinancing maturing debt will boost interest expense by 2% in 2024 and 5.5% in 2025

Source: Goldman Sachs

Reality check

But what about valuations? Can US earnings meet lofty expectations? Let’s look at how the market arrived here.

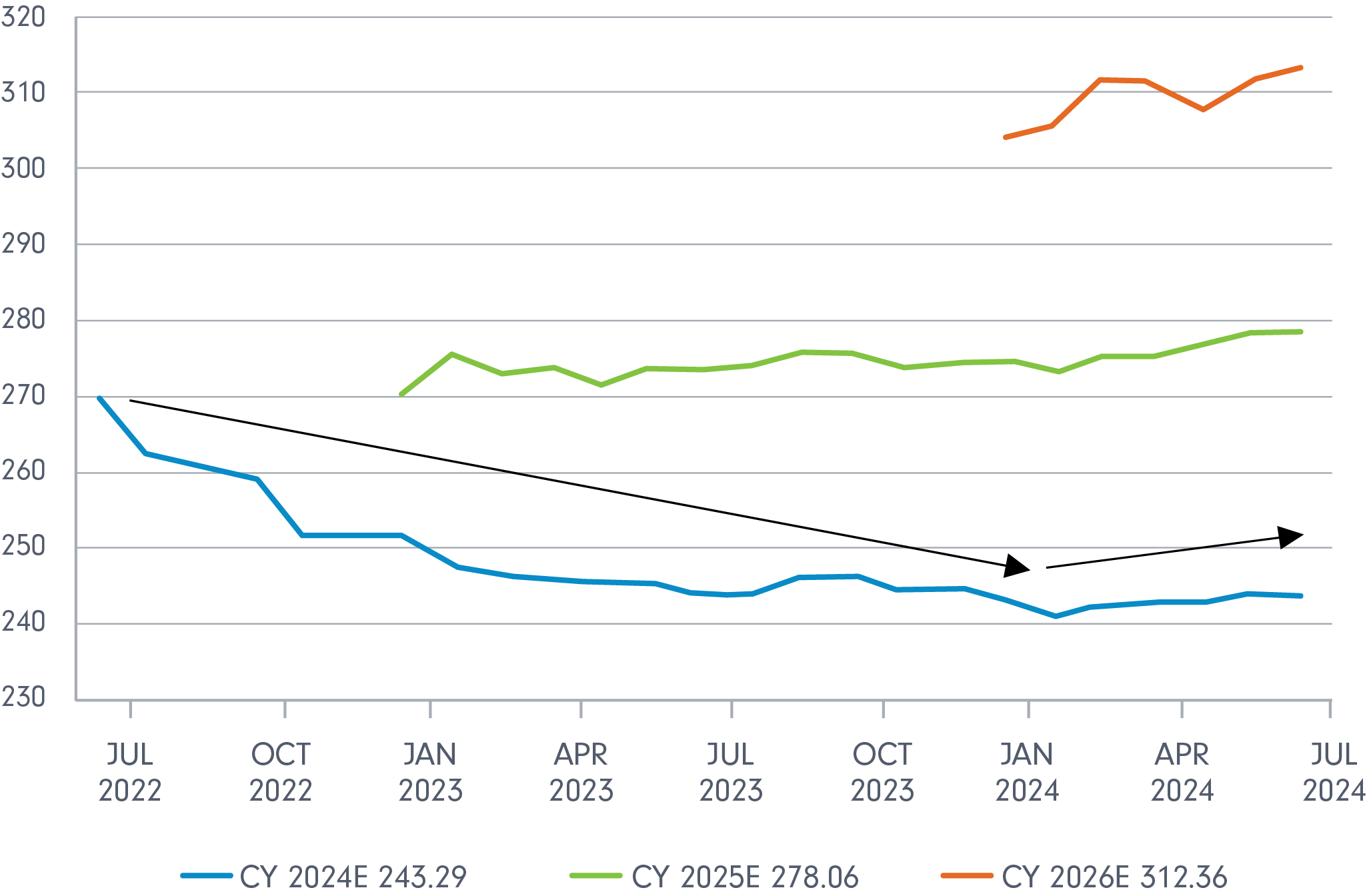

Once the market started to gain confidence a recession was no longer imminent, multiples expanded, reflecting the improving sentiment. This is shown in the chart below.

Chart 4: Market confidence increases

Source: FactSet, FIL

That’s quite typical behaviour when we see a recovery - first the multiples expand and then the company earnings reflect the multiple. However, if actual company earnings don’t catch expectations, the market is in a very vulnerable position.

Positively, on the earnings front, things are starting to look up. Having spent most of 2022 and 2023 being revised down, earnings estimates for 2024 are now actually being revised upwards, ever so slightly.

Chart 5: 2024 earnings estimates (S&P 500)

Source: FactSet, FIL

If reality delivers on expectations, 2024 earnings growth will be in the realm of double digits, which is clearly much better than the low single digit growth rates we’ve witnessed over the past few years.

It’s also worth mentioning that we are coming into the home stretch for the US presidential elections. Historically, the fourth and final year of the US presidential cycle has delivered above average returns, as both candidates typically announce a bunch of ‘sweetener’ policies aimed at winning over voters (think of tax cuts, big spending programs etc.).

Putting this altogether, the set up in the near-term (remainder of 2024) seems supportive of the US equity market, as the economy continues to hum along, and unemployment remains low.

However, investors are wise to remain cautious. Higher interest rates haven’t been able to have much impact in the US yet, and that these impacts could still come through later on. On that basis, I think it makes sense to make sure that portfolios remain focused on ensuring resiliency and survivability, whilst also maintaining a balanced exposure to the upside. A portfolio of high-quality businesses with strong balance sheets and secular growth opportunities, purchased at attractive valuations remains, in my opinion, the best place to be.

Sources:

- 1. Minutes of the Federal Open Market Committee March 21-22, 2023

- 2. Kennedy, Simon, “The Most-Anticipated Downturn Ever”, Bloomberg, 3rd January 2023

- 3. Zhou, Xiaoqing, “Existing low-rate mortgages blunt impact of recent rate surge”, Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, 27th December 2022

- 4. Hatzius et al, “The Corporate Debt Maturity Wall: Implications for Capex and Employment”, Goldman Sachs, 6th August 2023