Winning the hearts and minds of a generation of graduates - and the universities they attend - is the latest challenge facing the mining industry as it struggles to deliver the metals the world needs for the net zero transition.

In the search for a successful green transition over the next two decades, the world must consider investing heavily in mining. But after high profile campaigns against the damage done to the climate by mining activity there is growing evidence that a generation of graduate engineering and business talent has already decided it is not an industry they want to stake their careers on.

The potential shortage of skilled labour should be a concern not only in mining boardrooms but for anyone working to facilitate the net zero transition. Without engineers and geologists, that work will not succeed.

In the UK, universities’ career bodies are under pressure to cut ties with mining companies. A student-led campaign, which says it is active in dozens of UK universities, is targeting all fossil fuel and mining companies, aiming to disrupt their recruitment efforts. A college in London has already excluded mining and oil and gas companies from its career’s platform1.

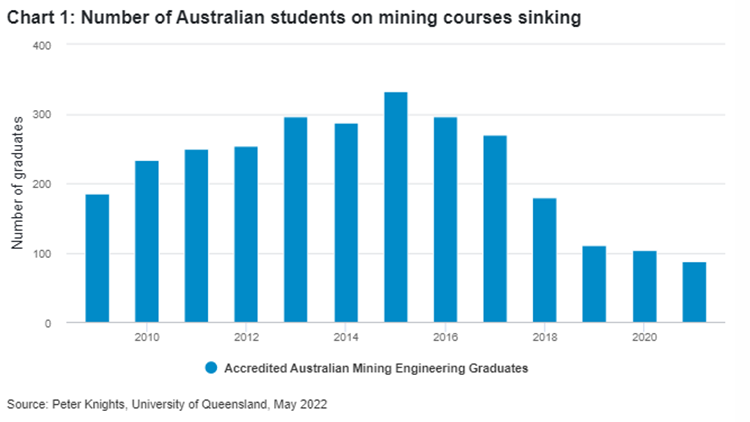

Meanwhile, here in Australia, the number of mining engineering graduates has fallen by an extraordinary three quarters since 2015, according to data compiled by the University of Queensland in a study in partnership with the Minerals Council of Australia. Two of the country’s main university programs have closed as a result. Professor Peter Knights, who carried out the research, estimates that Australian universities are now producing fewer than half the engineers needed to meet the country’s current needs, let alone any future expansion. This has led to the Minerals Council of Australia launching an image management campaign to reposition the industry and remedy the recruitment problem.

The trend is perhaps understandable. Large parts of Australia’s thermal coal industry must be closed, creating an obvious limit to any career. Some mining companies also have poor reputations for polluting the atmosphere and damaging ecosystems. Students assume work in the sector will be “dirty” and will tend to take them far from friends and family2. Some 94 per cent of students surveyed say job security is important when choosing a career; only 12 per cent think jobs in the mining industry are not in decline.

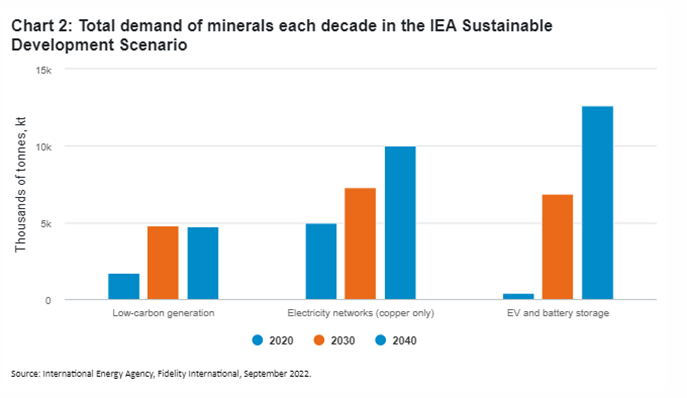

But as we wrote in the paper "The decarbonisation and mining paradox" earlier this year, demand for metals and other mined commodities will actually have to grow spectacularly over the next 30 years for the world to decarbonise. Materials like nickel, lithium, rare earths, and cobalt are used in electric vehicles, wind turbine gears and generators, and energy storage. The infrastructure needs of this revolution, often forgotten, also imply significant demand for metals such as steel, and its mineral component iron ore. Overall, the International Energy Agency (IEA) predicts that demand for minerals needed for electricity networks will double, while that for electric vehicles and batteries will grow by 10 times or more.

A mining industry shorn of talent risks botching the transition. Balancing the urgent need for minerals against the environmental costs of extracting them is challenging enough at today’s levels of demand. As production expands both the carbon and social impact will need to be reduced. Eye-catching improvements like British miner Anglo American’s hydrogen-powered truck, unveiled this year, must be accompanied by the more prosaic business of steadily decarbonising each piece of the supply chain. Without skilled engineers, that promises to be difficult.

We need miners

In that context, stymying recruitment to the mining industry is a step backwards. Environmental and climate change activism has an important role to play in raising awareness, but its big, simplistic, high-impact messages have succeeded in demonising the industry. Activists often group mining along with oil and gas, but these are not the same. One is crucial to delivering the transition, the other will likely be a long-term loser of that same transition.

Universities can help educate and provide much-needed nuance, highlighting the importance of mining investment to the transition, and attracting and training the talent that will innovate in the years ahead to make production more responsible and cleaner.

Responsible investors can play a part by looking for miners that not only meet stringent environmental criteria today but that have high potential to do so in future, and who are open to change. Students and new graduates should be at their heart. Without them, we will all suffer.

Sources:

1: People & Planet's Fossil Free Careers Campaign | People & Planet (peopleandplanet.org)

2: “Student Perceptions of a Career in Mining”, Minerals Council of Australia