Key points:

- We believe a Disorderly (or Delayed) transition is the most likely scenario as net-zero carbon emissions by 2050 now look out of reach.

- Estimates suggest the impact of severe weather on global growth will be larger than previously believed.

- Markets find it challenging to reflect risks and opportunities that may play out far into the future.

- Investors still underestimate climate risks, partly due to the challenges associated with predicting potential impacts.

- The effects of the transition on share prices will vary by region and market sectors, given that climate activity will boost investment and revenues across certain industries.

- We feel climate risks will have a relatively limited impact on fixed income returns, and attractive income levels may balance any losses.

Policymakers and the markets may still underestimate climate risk, even as the world heads for a Disorderly transition to a low-carbon economy. Against this backdrop, it’s more vital than ever to understand the impact of climate change on investment strategies and integrate robust risk-management processes into portfolios.

An Orderly transition to a low-carbon economy, placing the world onto a Net Zero 2050 pathway and confining the global temperature increase to 1.5 degrees Celsius, remains possible but, realistically, appears to be out of reach.

Businesses recognise that reducing their carbon footprint while complying with increasingly strict regulations will prove more difficult than thought. And while there has been an encouraging acceleration in the technology needed to assist with the transition, that pace will have to quicken.

From a financial perspective, adapting an investment process to this challenge is also complex. Market participants must consider various climate outcomes and predict how they will affect economies and businesses. To date, investors have found that pricing in highly uncertain risks and opportunities that may play out far into the future is somewhat problematic.

At Fidelity International, we continually seek to understand how short- and long-term transition risks will shape the financial landscape so that we can improve the decision-making process and help our clients integrate climate risk into their portfolios. To that end, we track environmental developments in real time, harnessing the latest climate-change research and updating our Sustainable Investing Framework.

Fidelity’s framework is based on the four climate scenarios the Network for Greening the Financial System (NGFS) mapped out. In order of attractiveness, these are Orderly, Disorderly, Too Little Too Late, and Hot House World.

Where we stand in 2024

A Disorderly (or Delayed) Transition scenario is currently the most likely, though Too Little Too Late and Hot House World are also moving closer.

A Disorderly scenario assumes that annual greenhouse gas emissions will not begin to decrease until at least 2030. Even if that does happen, stricter rules and regulations will be needed to limit warming to less than 2 degrees Celsius.

The increased likelihood of a Disorderly Transition is the result of multiple factors: insufficient progress made in recent years, the growing complexity of implementing the transition, awareness that the physical impacts of climate change will be worse than previously thought, and the persistence of high energy emissions into the near future.

Without more immediate and intense government policy responses and more ambitious transition efforts across all sectors of the economy, we face two critical areas of risk – physical risks and transition risks.

Physical risks are the longer-term risks relating to the impact of climate change on economies.

It is now suggested that the effects of extreme weather on global growth will be worse than previously believed. The latest predictions include two notable hazards – droughts and heatwaves – that have more significant economic consequences than floods and cyclones. Europe, Asia, and Australia are the most vulnerable regions, while North America is the most resilient.

Transition risks relate to the impact of moving away from carbon-intensive operations on countries and companies.

The distribution of these risks is uneven. For instance, those countries or businesses facing the biggest short-term transition-related risks are not always the same as those dealing with the largest long-term physical risks. As a result, governments and companies may be less willing to face significant short-term pain in return for long-term gain, even though by delaying the transition, they will potentially endure more severe physical impacts.

A case in point is the net-zero carbon emissions by 2050 scenario. Europe and the United States face the highest transition risks because their economies are more vulnerable to short-term growth sacrifice. At the same time, Asia and Australia would reap the benefits of reducing physical risks associated with the transition.

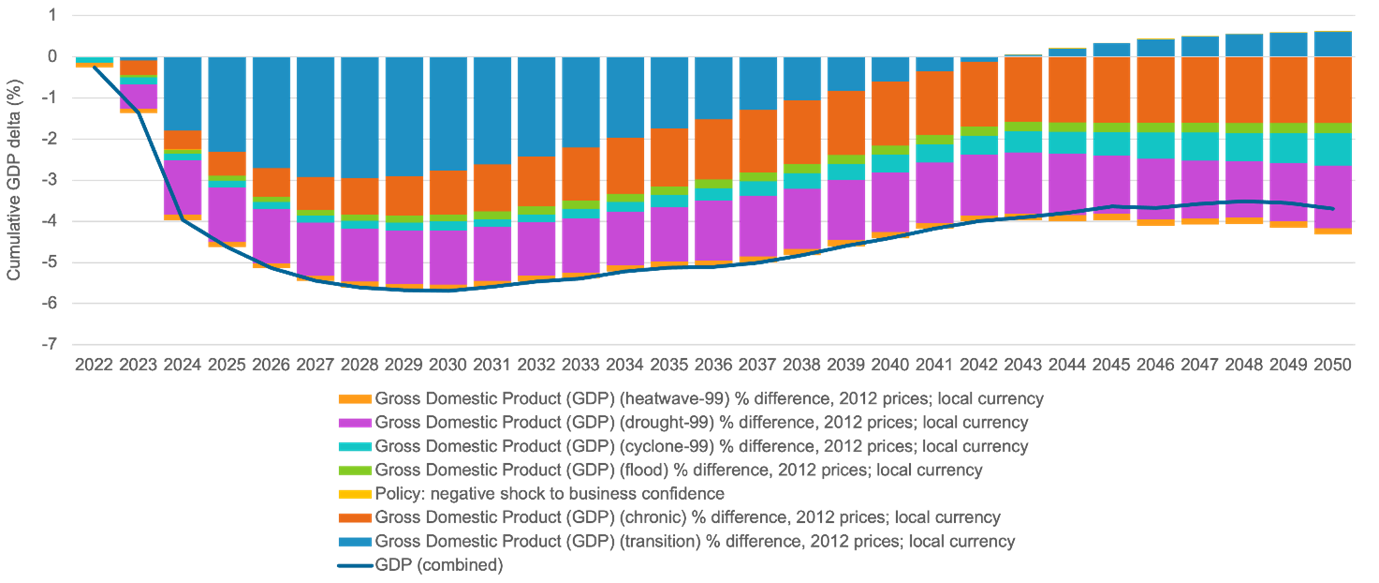

According to estimates, if the US followed the net-zero carbon emissions by 2050 roadmap, the negative impact on its gross domestic product (GDP) growth would peak at about 5.7 per cent by 2030, after which the economy would gradually recover (see Figure 1).

In a Delayed Transition scenario, the economic damage to the US would take longer to peak but be more severe and longer lasting.

In Europe, the long-term consequences of a Delayed Transition are forecast to be even more pronounced, with total GDP losses increasing to about 9 per cent by 2049.2

Figure 1. US GDP impact in a Net Zero 2050 scenario: 99th percentile acute risks

For illustrative purposes only.

Source: NGFS Phase IV Net Zero 2050 scenario, Fidelity International, April 2024. Results are preliminary.

The effect of a transition on asset classes

Stocks – The transition and physical risk combination will likely harm equity returns across all four possible scenarios (Orderly, Disorderly, Too Little Too Late, and Hot House World). That said, the effects will vary by region and market sector, given that transition-related activity will boost investment and revenues across certain industries helping tackle climate change.

Any adverse effects of an Orderly transition on equity returns will be more significant in the initial decade of the changeover. In contrast, the physical risks of a Disorderly transition will create a bigger impact over the longer term.

Fixed income – We believe climate risks will have less impact on fixed income returns, as higher income levels will balance price impacts and credit losses. An Orderly scenario could positively affect returns, primarily because of the consequences of higher inflation on interest rates and bond returns.

Overall, given the uncertainty surrounding which climate scenario will emerge and how it will play out, we believe, as ever, that rigorous investment research and bottom-up insights across markets, industries and regions can help investors navigate the transition by softening climate risks through time.