A key driver of environmental, social and governance (ESG) flows (total assets under management are now US$1.97trn1) continues to be regulation. The latter is responding to the increased frequency and materiality of ESG-related events, attempting to shape the direction of travel and how these issues are managed.

Climate change, cyber security breaches, enhanced focus on racial equity, the drive for “common prosperity” in China and the need to restore and preserve biodiversity have all pushed regulators and policymakers to act.

The resulting wave of rules and incentives are designed to:

- improve risk management

- accelerate funding towards solutions

- enhance consistency and availability of sustainability disclosures.

Below we look at some of the key regulations and policies affecting corporates and financial services, and their implications.

Corporate disclosure is high on the regulatory list

Towards the top of the regulatory list is the race to improve corporate disclosure. The European Union (EU) is set to implement its comprehensive Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) to support its attempt to reduce emissions by 55% by 2030. The regulation requires a large proportion of firms, including private companies, to disclose against a new set of European Sustainability Reporting Standards. These seek to embed the concept of “double materiality” by requiring companies to report on metrics, including climate change, biodiversity, circular economy, human rights, and labour conditions, that have a financial impact on the company or an impact on the environment and society.

At the same time, the International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB) is creating a general sustainability (S1) reporting standard and a climate (S2) reporting standard as a global baseline for sustainability reporting, which it hopes will be adopted by regulators and companies globally. The ISSB has adopted an “investor useful” materiality assessment and has indicated it is working with the EU and other jurisdictions to try and align disclosures for companies as much as possible.

The ISSB has integrated existing TCFD metrics into its climate disclosures to make it easier for companies already using TCFD to adopt ISSB standards. The ISSB’s proposed disclosures have received robust support within Asia and will likely see a phased adoption with an initial focus on S2 given higher compatibility with existing climate disclosure regulations within the region.

The Securities and Exchange Commission in the US meanwhile is expected to finalise its climate disclosure rules in 2023, which include detailing climate risks that have a financial impact and greenhouse gas emissions reporting.

As a result, we expect sustainability disclosures to increase and begin to be considered more systematically alongside company results. That said, it will take time for companies to build capacity to capture the required data and for consistent methodologies to develop. We note that nature frameworks such as that proposed by the Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures (TNFD) are still in development.

While a richer data environment is helpful, data alone is not the silver bullet for managing sustainability issues. Fidelity’s fundamental investment heritage provides a foundation for its global analyst network and Sustainable Investing team to engage with issuers not only to help bridge data gaps, but to generate actionable insights and drive positive change.

Fund disclosure is a close second

A close second behind corporate disclosure is investment ESG disclosure. In Europe, investors have been implementing the Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR) since it became applicable in March 2021. Funds with sustainability considerations are required to make specific sustainability disclosures. While SFDR was intended to focus on disclosures, the measures have been adopted by the market as a de-facto labelling regime. EU regulators are now looking at ways to improve SFDR including whether to apply fund labels and minimum investment thresholds.

The UK aims to implement a labelling regime under its Sustainability Disclosure Requirements (SDR). Under the proposals, UK funds could only market themselves as sustainable if they opted for one of three labels: sustainable focus, sustainable improvers, and sustainable impact - all of which come with specific investing and stewardship criteria that are still under discussion.

In Asia Pacific, ESG product labelling rules have been introduced in Hong Kong, Singapore, and Taiwan and are under development in South Korea, India and Mainland China. While Australia does not have a regulatory ESG product labelling regime, the local regulator ASIC has stepped up its focus on preventing greenwashing via enforcement.

Fidelity continues to work with industry associations and regulators globally to help promote practical, harmonised, and informative fund disclosures and requirements.

Taxonomies prove a popular tool

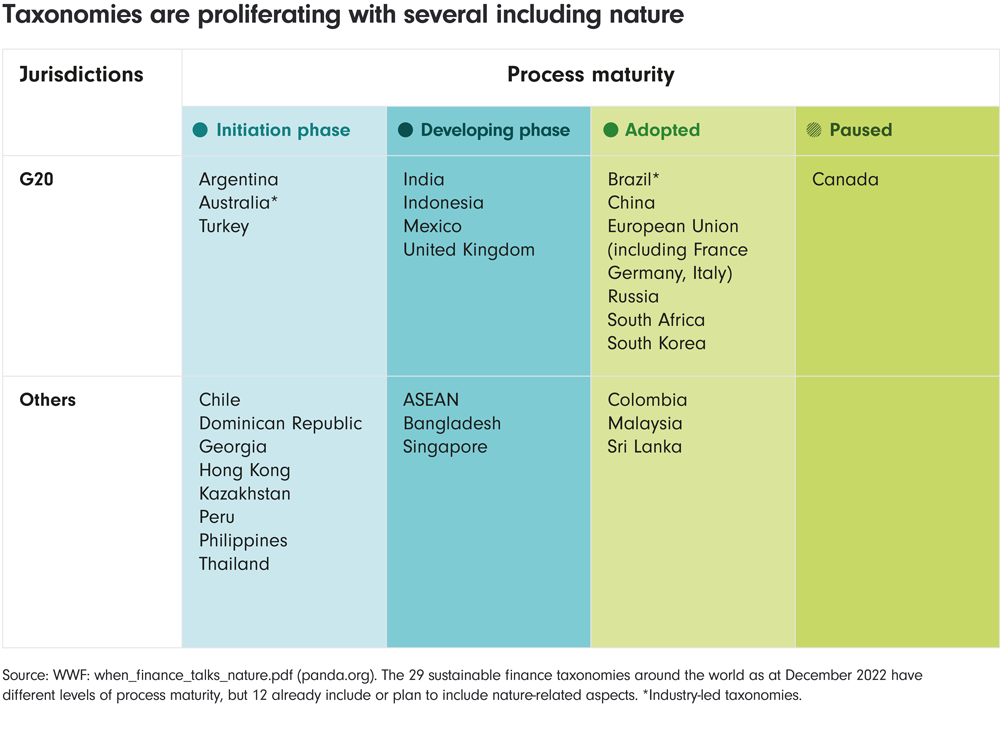

Another tool in the regulatory toolbox is having a green taxonomy, which is proving to be popular globally. According to a December 2022 report by WWF, several countries have adopted taxonomies and many others are developing guidance, with 12 including or planning to include nature-related aspects. China and the EU are among the most developed but reflect the different priorities for their economies. For example, China’s taxonomy has a bigger emphasis on agricultural activities. In the UK, the taxonomy has been delayed until the autumn. Green taxonomies have recently been launched for ASEAN, Singapore and Malaysia; each has different standards and approaches to identifying ‘green’ investments.

These differences create a risk of fragmentation in what is considered green globally. However, it is worth noting the example of the EU-China Common Ground Taxonomy which was developed to highlight commonalities and differences between the two taxonomies and facilitate international sustainable investing. Over time, it is possible that taxonomies will begin to be interoperable if not fully harmonised.

Transition on the horizon

While regulation is on the rise, policy is also being made. The US has launched its Inflation Reduction Act, a massive incentives programme that is making emerging technologies such as hydrogen and batteries economic with fossil fuels and prompting policy responses from other regions and countries who wish to compete in the race to build green industries and services.

Possibly even more effective over the long term is the growing demand for companies, investors, and even governments to adopt clear, credible transition plans. Transition plans aligned to 1.5°C are part of requirements for EU companies under the hotly debated proposed regulation known as the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive. The proposed rules could make directors and companies liable for prosecution if they fail to show they have done all they can to mitigate and prevent environmental and social harms, including having an insufficient transition plan.

Meanwhile, the UK Transition Plan Taskforce has proposed a broad framework for transition plans that require companies to disclose how they are adapting their business strategy to decarbonise their operations and lean into a whole of economy transition. The UK is seeking to encourage adoption of the framework around the world and transition plans could become mandatory in the UK.

While the regulatory wave can appear somewhat daunting, at Fidelity, we are supportive of the focus on the transition to net zero and sustainability more generally. We continue to engage with regulators and policymakers to build the most favourable policy environment for our investee companies to make the transition and for us to be able to provide sustainable products for our clients.

Source: 1. Broadridge/Fidelity. ESG funds are Fidelity’s Sustainable Fund Family and those in the industry classified as ‘Responsible Investment - Screened” by Broadridge. Includes all active & passive funds globally except those primarily sold in North America. Excludes money market and fund-of-funds