Demand for some of the real assets neglected over the course of the pandemic has the potential to surge as the world shifts to a new, sustainable paradigm, but there will be more pain elsewhere.

It is more than 18 months since Goldman Sachs raised the prospect of a new commodities "supercycle" and, while the war in Ukraine has muddied the waters, the broader case for a longer period of high prices for commodities has not weakened. As they were in the decade before the 2008 global financial crisis, the needs of the green transition mean that certain raw materials are, and could continue to be, massively in demand. That has the potential to underpin a long surge in the prices of metals like nickel, cobalt, and lithium that are key inputs in the electrical infrastructure the world needs, alongside a repricing of carbon. If this continues to prove true, investors are facing a new paradigm.

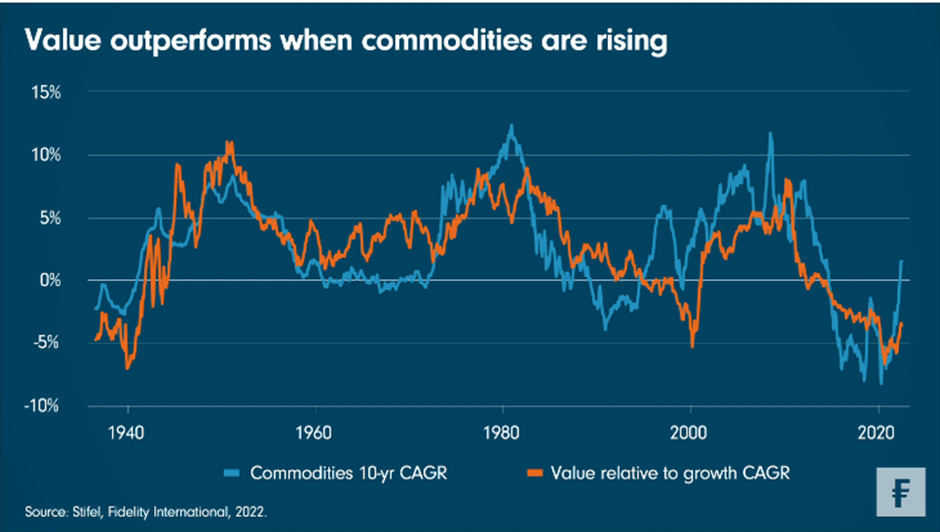

Historically, as this Chart Room shows, when commodities do well, 'growth' stocks - including tech and many others that have soared during the global recovery from the pandemic - tend to do less well than 'value' plays like financials or consumer staples. The same is true of the S&P 500, which historically tends to go in the opposite direction to commodities prices. Think old economy versus new. Or providers of ‘core’ services, not ‘added value’ ones.

The jury is still very much out on the supercycle theory, and things could get choppy along the way. The oil market tensions of the past six months could ease. A hard landing for the global economy could suck commodities prices backwards. Investment in oil and gas in the Middle East and the United States could rebound.

But environmentally, large parts of the world do seem set on a course which demands the same sort of radical change in cities and infrastructure as China’s growth in the 2000s or the reconstruction of Europe and Japan in the 1950s. If that happens the cost of living crisis may be here to stay for some time as structural inflation beds in, but also that investors will potentially be rewarded for allocating capital toward the green transition: investment in electrification, in new heating systems for homes, in new transport systems and new ways of growing and packaging food, for example.

Along the way, we might also cleanse the financial system of misallocation of capital due to a decade of central bank largesse. Real assets are likely to profit at the expense of financial assets; and many of these bubbles are already bursting. That will not be easy, but regime change never is.