Jump to the bottom to watch the short video

From 3-5 November, we hosted our annual Fidelity Investment Conference, whose theme – delivered this year in a virtual setting – was “Finding opportunities in a post-pandemic world”.

On Day 2, Jenn-Hui Tan talked about sustainable investing, and how in 2020 it went mainstream across all sectors in the financial industry.

This year proved pivotal for the environmental, social and governance (ESG) movement, said Jenn-Hui Tan, Fidelity International’s Global Head of Stewardship and Sustainable Investing, with sustainable investing now “too big for any of us to ignore”.

A sustainable economy, he explained, is one in which negative impacts are minimised, and in which firms ideally have a positive impact on the environment and society. Although the features of such an economy vary, they can include: lower or negative carbon emissions; the circular use of natural resources; fair treatment of workers and other stakeholders; ethical business conduct; and producer and product responsibility.

Those are among the considerations driving Fidelity’s approach to investing, as it directs capital in favour of businesses that can contribute to that sustainable economy.

“That in turn reduces their cost of capital, enhances their competitiveness and facilitates a just transition from an extractive economy to a regenerative economy,” he said.

To that end, Fidelity integrates a range of ESG factors with a long-term investment process, while favouring engagement over exclusion. Its sustainable investing approach has proven its value, Tan notes.

.jpg)

The global rise of ESG

For several years, Fidelity has asked its analysts whether they have seen an increased emphasis among the companies they cover to implement and communicate ESG policies. As recently as 2017, that was not the case for most companies.

“But fast-forward to 2020, and that number is vanishingly small. The overwhelming majority of companies are now focused on disclosing and communicating ESG policies,” Tan said, adding that this trend was true across the world, and that ESG was not simply a “developed-market concern”.

“Our data shows that, right across the world – in China, in Japan, in Asia-Pacific, in the ASEAN region – the priority on ESG has gone to the forefront of our companies’ minds.”

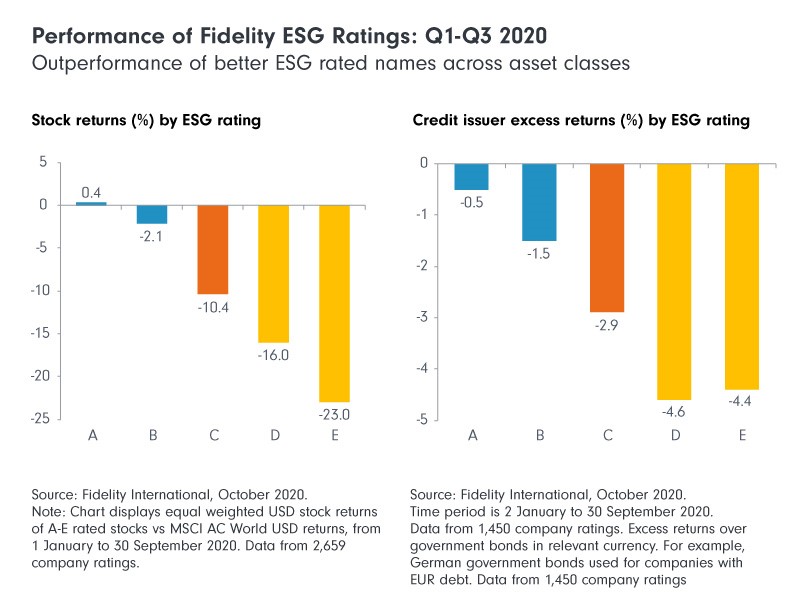

The COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated the trend, in part because the crisis has proven the value of ESG research and ratings. Over a six-week period following the onset of the pandemic, during a period of intense market volatility, Fidelity saw a clear correlation between a company’s ESG rating and its performance relative to a benchmark. That relationship held across equity and fixed income, and remained valid after Fidelity updated its research to cover the first three quarters of 2020.

.jpg)

“That underpins our view that ESG is a factor that works in both market-volatile times – in down markets – but also in the strong market recovery we’ve seen since that initial period of volatility,” Tan said.

In Fidelity’s view, this outperformance is because ESG factors are a crucial indicator of a company’s resilience and robustness, which is in turn a sign that the firm has a forward-looking management team that takes a long-term view of risks and opportunities.

The results also countered the view of many that ESG was a bull-market phenomenon, and that investors would discard ESG and focus on financial returns once a bear market returned.

Not so, said Tan.

“ESG has now become paramount in the minds of our investors and our clients. And so, in that sense, I think we can say with confidence that ESG has passed its first live test.”

Purpose-led corporations

Beyond proving the financial value of ESG, the pandemic has had a more profound impact in refocusing corporate attention on the importance of being a purpose-led business: “To serve the needs of society by providing a valuable product or service, and to do so in a way that minimises its environmental impact and accentuates its positive societal impact.”

Generating a profit should be seen as the by-product of a firm successfully fulfilling its purpose, said Tan, adding that the Business Roundtable – a U.S.-based non-profit coalition of CEOs of the country’s largest corporations – had endorsed this change of view of a firm’s purpose in 2019.

“That was an important recognition of the fact that creating short-term and medium-term value for stakeholders is the most reliable way to create long-term value for shareholders,” Tan said of the coalition’s statement.

Specifically, the pandemic has accelerated the focus on the social factor of ESG, a shift from the previous priorities of environment and governance. The social factor is a reflection of a company’s basic societal license to operate. Measuring social factors – like how firms treat their suppliers or how `their products are used by and marketed to their consumers – has traditionally been considered difficult, Tan said; after all, how does one quantify a company’s culture?

“But the rise of big-data sets and alternative sources of information now allow us to find information about a company – not just information that is published by a company,” Tan said, adding that this data can be integrated into investment analysis and decision-making.

Doing so has become increasingly important, given the heightened risk of brand damage for companies that engaged in anti-social behaviour, regardless of whether they operate in consumer-facing sectors or not – as shown by the case of Rio Tinto in 2020, when a decision which resulted in the destruction of a cultural heritage site in Australia culminated in the resignation of the firm’s CEO and two senior executives.

The shift from shareholder capitalism to stakeholder capitalism is borne out in how companies globally have sought to ease the difficulties their stakeholders have encountered. Some have made their products more accessible to consumers, for example, while others pay suppliers faster and ensure they retained long-term contracts.

Social factors and future actions

Tan said the focus should be on three core areas as the world looks to “build back better”.

The first is the millions of workers in supply chains for whom life has become much harder. That includes migrant workers, textile workers and seafarers, 400,000 of whom “are trapped aboard…and not permitted to embark and disembark and do crew changes”.[1]

“Ninety percent of global trade moves by ships. None of us would be sitting here at home with our food, with our energy, with our security, without their work,” he said. “Their solution needs a truly multilateral approach from all parts of the value chain.”[2]

The second area, and one that will become increasingly important, is digital ethics. This requires assessing the role of platforms, around which many people’s online lives coalesce, in ensuring positive societal outcomes for users. Considerations include fake news, data privacy, cyber-bullying, fraud, and the way algorithms function to draw in users and retain them. The investment risks, Tan said, were clear, with platforms facing an existential risk should they fail to consider those risks and lose trust among their users.

“Top of the list is future regulation – future regulation here is almost inevitable,” he said, given global governmental focus. “But regulation will come too late. Companies must be encouraged to self-regulate.”

The third area, which the pandemic has highlighted, is how human society has pushed back against the boundaries of the natural world, generating feedback loops that affect societal sustainability. Climate change, the loss of the Antarctic ice sheets and the availability of the Amazon rainforest were interconnected, Tan said, and could create feedback loops “that may be irreversible if we don’t act immediately”.

Tan noted that the destruction of natural capital was an ecological and financial disaster, with half of the world’s GDP, some US$44 trillion, “moderately or highly linked” to its availability, according to the World Economic Forum. Firms are working to quantify, disclose and assess exposure to nature-based risk, with this approach borrowing from the Taskforce for Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) framework, which assesses climate-related financial risk.

“Ultimately, the underlying issue here is that we as a society, as an industry, need to learn how to price natural capital better,” he said, adding that doing so on the existing input basis was insufficient.

“What we need to learn to price is the sustainability of natural capital – because simply putting these things as inputs is resulting in a process where their long-term value is being eroded because they cannot then be replaced,” Tan said. “And so that now needs to be factored into our financial models, and that is the challenge for Fidelity – and a challenge for the financial industry over the next two to three years.”

[1],2 International Chamber of Shipping