While it could be argued that economic activity in the US and China has contributed more than its fair share to the climate crisis, both countries are also working hard to develop effective long-term solutions that will reduce emissions levels. The key to a successful green transition will be directing capital from the developed world to emerging markets.

Missed the Summit? Watch the replay

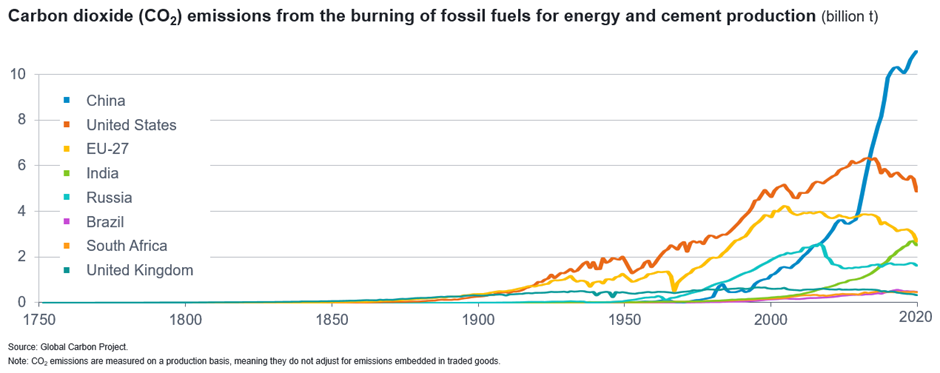

According to research published in 2021, China and the US collectively account for 38 per cent of global greenhouse gas emissions. By comparison, the 27 member states of the European Union contribute 6.4 per cent[1]. In particular, China’s economic growth has mainly been coal powered, which between 1985 and 2016 was responsible for almost 70 per cent of the country’s energy use[2]. Indeed, it still represents around 60 per cent of the fuel burned for electricity production[3].

This demand for coal has been sustained by China’s drive toward urbanisation, with the industrial sector demanding unprecedented levels of steel and cement. To put this into perspective, between 2011 and 2013, China produced and utilised more cement than the US did from 1901 to 2000[4].

Against this backdrop, the cost of decarbonising the global economy, from buildings to farming and transport to finance, is estimated at US$4.8 trillion a year from now until 2050. A total bill of US$144 trillion[5].

Behind the headlines

“It’s worth pointing out for context that current emissions only tell one side of the story,” says Jenn-Hui Tan, Global Head of Stewardship and Sustainable Investing at Fidelity International. He notes that at 7.4 tonnes, the average Chinese consumer's annual per capita CO2 emissions are around half of their US equivalent who produces 14.2 tonnes[1]. Looking at the longer-term picture, the US has been responsible for 20 per cent of cumulative global emissions since 1850, with China at 11 per cent[2].

Policy-led approach

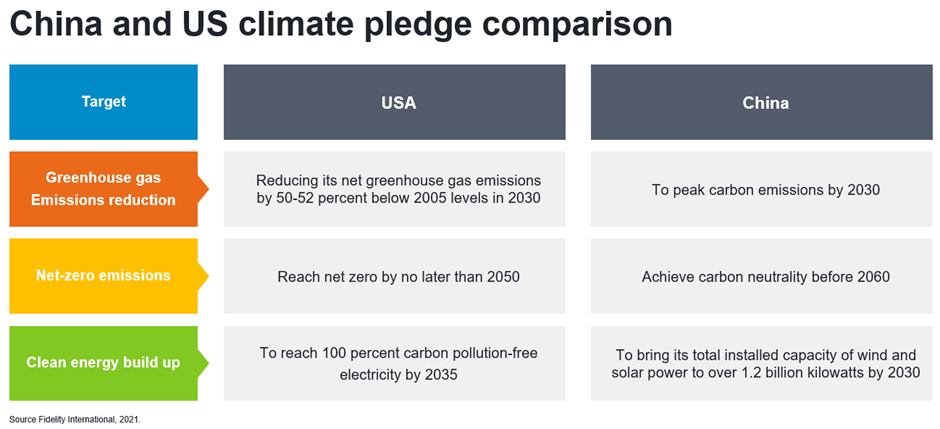

The governments of China and the US have recognised the issue at hand and made broadly similar commitments to achieve their climate goals. “It was clear from the start that the Biden administration would treat the climate as a priority,” says Tan. US President Joe Biden has pledged to cut US emissions in half by 2030, from a 2005 baseline, and committed the US to reach net zero by 2050[3].

One of Biden’s first acts as president was to re-join the Paris Agreement, with its pledge to limit global warming to well below two degrees Celsius. He then established a government-wide programme aimed at tackling climate change.

Amid the COP26 climate change conference in November 2021, a US$1.2 trillion bipartisan infrastructure bill was passed that included the most significant investment in clean energy transmission in US history[1]. This was augmented by President Biden’s Build Back Better agenda that earmarks billions of dollars for investment in decarbonisation, including clean energy, as well as the promotion of clean technology and green-material manufacturing in the US.

A vested interest

In China, President Xi Jinping has committed the country to be net zero before 2060. He also wants to reach peak carbon emissions by 2030[2]. Although the latter is not a 2050 commitment, it represents a carbon peak-to-trough period of 30 years that would be a significantly faster national decarbonisation than any other major country has achieved.

China has what Tan calls “a clear and vested interest” in dealing with climate change.

He points out that more than 40 per cent of China’s population and gross domestic product (GDP) is centred around the Yangtze River economic belt[3]. Furthermore, with over 100,000 square kilometres of the country’s coastal area sitting 10 metres below sea level, it is already experiencing physical climate change events. Most recently, there was severe flooding in southern China that affected almost 60 million people[4].

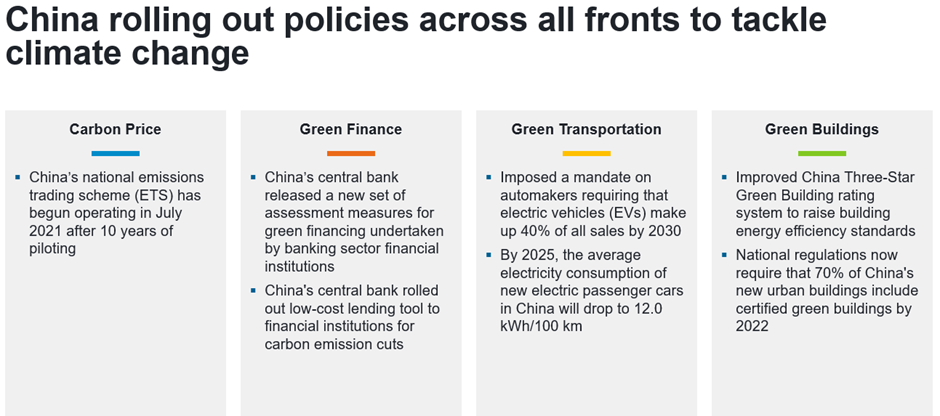

China has already rolled out several policies designed to tackle a changing climate, including the world’s largest national emissions trading scheme, which now captures 40 per cent of the country’s carbon dioxide emissions[5]. There have also been supportive measures from The People’s Bank of China that seek to promote renewable energy. In fact, renewable energy in China now accounts for around 30 per cent of its energy output, and the country also provides half of the world’s renewable energy installations[6][7]. Domestically, China aims to have a total installed wind and solar power capacity of more than 1,200 gigawatts by 2030[8].

Re-directing capital

“Technological innovation is key to reaching net zero,” observes Tan, who maintains an optimistic outlook. “Venture capital and private equity activity among climate tech startups are at historically high levels,” he continues.

While there is significant support for alternatives, such as nuclear power, green and blue hydrogen, renewable infrastructure, as well as carbon capture and storage, “a better alignment of investment capital and investable projects is needed,” he adds.

According to Tan, the challenge is “to direct capital from the developed world toward emerging markets, which will enable the green transition to happen.” He observes that most financial assets are in developed territories. At the same time, most of the capital needed to meet sustainable development goals should be aimed at emerging markets.

“Private sector capital flows and public-private partnerships must deliver financing if emerging economies are to decarbonise,” he continues.

The Joint Declaration of the US and China on climate action announced at the end of COP26 is significant because the announcement showed that climate is one area “where the two countries can work effectively in unison,” explains Tan.

Decarbonising investment portfolios

Climate-focused initiatives aren’t the exclusive domain of governments and policymakers. Investors in the US and China are playing their part too. This is being demonstrated by the growing trend of portfolio decarbonisation. Leading asset managers, for example, already have ambitious plans to slash the carbon footprints of their investment portfolios by the end of the decade. But, as Tan notes, “This is more than a 10-year plan. Truly ethical investing is a longer-term process and one that will ultimately hold businesses to account.”

Many asset managers have excluded entire sub sectors, such as thermal coal. While this is an essential first step, it’s crucial to recognise that the decarbonisation process is a lot subtler than easy-to-apply blanket exclusions. “Asset managers can’t simply remove a block of companies then sit back, pleased with their work,” adds Tan. It’s vital to scrutinise individual holdings within a portfolio to identify more deeply embedded climate risk. For instance, firms that are not aligned with the pledge to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius or those that show an unwillingness to adopt ESG-friendly business practices. “In saying that, ethical laggards should not be dismissed out of hand. Investors need to engage with corporate management teams to encourage change. It’s an evolving process,” he concludes.

[1] Source: BBC/Rhodium Group

[2] Source: China Power

[3] Source: Reuters

[4] Source: Forbes

[5] Source: Fidelity/Goldman Sachs

[6] Source: Our World in Data

[7] Source: Carbon Brief

[8] Source: The White House

[9] Source: The White House

[10] Source: Bloomberg

[11] Source: Xinhuanet

[12] Source: Times of India

[13] Source: CarbonBrief

[14] Source: Argus Media

[15] Source: SCMP

[16] Source: Bloomberg