At the United Nations (UN) Climate Change Conference (COP 27), overall progress across a broad range of climate issues was inconsistent at best. The only real progress was made with the announcement of a dedicated loss and damage (L&D) fund, to support developing countries who have been particularly vulnerable to climate disasters. At the other end of the scale, very little progress was made on emissions reduction measures to meet the 1.5°C target.

The financial implications of climate change are not only going to be felt by developing countries; wealthier nations will also have to foot the bill for the consequences of unmitigated climate change. Estimates from the World Economic Forum suggest that global GDP could be hit by 14% were we to see a 2.6°C temperature increase. Yet, according to the UN report released before COP 27, current pledges put us on course for 2.1-2.9°C warming by the end of the century.

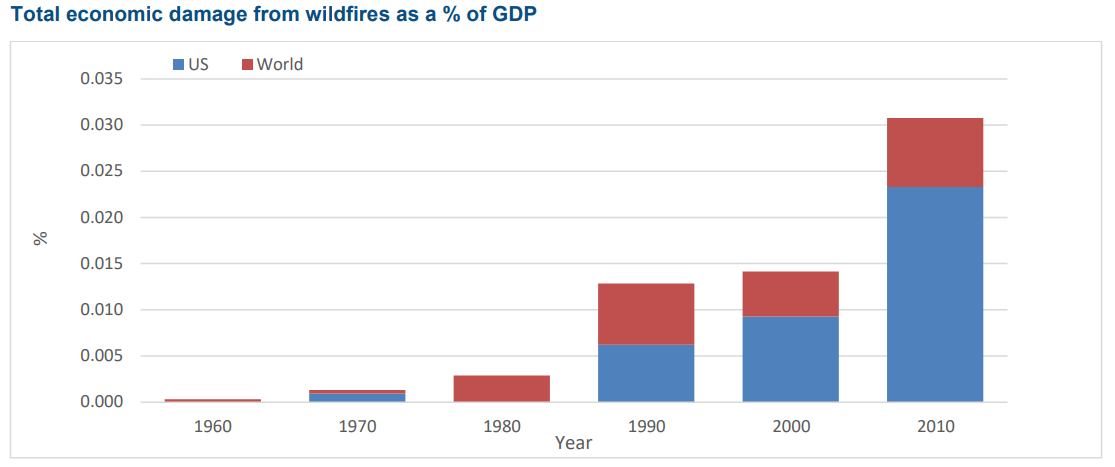

Source: Our World in Data based on EM-DAT, CRED / UCLouvain, Brussels, Belgium – www.emdat.be (D. Guha-Sapir). Note: Decadal figures are measured as the annual average over the subsequent ten-year period. This means figures for ‘1900’ represent the average from 1900 to 1909; ‘1910’ is the average from 1910 to 1919 etc.

At Sharm El-Sheikh, a broad consensus was reached, one which recognised the financial implications of not acting to mitigate climate change. Yet little progress was made on stepping up the pace of emissions cuts to address the root causes of climate change.

Climate stakeholders continue to make progress, regardless of COP 27’s inaction

It is undeniably disappointing that COP 27 did not provide any significant progress to a credible 1.5°C outcome, but in a wider context we have observed significant momentum from other climate stakeholders. Individual governments, corporates, investors and consumers are increasingly taking pre-emptive action, whether that be legislative action by lawmakers or investment decisions by corporates independent of subsidies or changes in multinational environmental legislation.

At the national government level, the United States recently enacted its Inflation Reduction Act, with US$369 billion in energy security and climate change investments, designed to cut carbon emissions by roughly 40% by 2030. This is a transformational piece of legislation which we believe will dramatically accelerate the prospects of many decarbonisation technologies: electric vehicles, green hydrogen, carbon capture, renewables, and energy storage to name a few. The Act also provides powerful economic incentives to kick start early-stage industries, such as green hydrogen or carbon capture.

Companies traditionally associated with high emissions are increasingly taking responsibility by transitioning to a low carbon environment, rather than face environmental externalities and the negative impact on their earnings.

German cement giant Heidelberg Cement has developed the world’s first industrial-scale carbon capture and storage project at a cement production facility at Brevik in Norway. When fully operational in 2024, 400,000 tonnes of CO2 will be captured annually and transported for permanent storage. Cement production is among the biggest contributors to climate change and is responsible for around 8% of global carbon emissions.

Danish shipping company A.P. Moller - Maersk is also doing its part by accelerating decarbonisation within its fleet, offering customers climate neutral transportation. The firm recently announced an order for another six large ocean-going container ships with dual-fuel engines, enabling them to operate on green methanol – resulting in a combined saving of about 800,000 tonnes of CO2 emissions annually. Global shipping emits around 3% of worldwide greenhouse gases (GHG).

In areas such a plastic pollution where legislation is broadly light touch and fragmented, organisations such as the Ellen MacArthur Foundation are mobilising entire industries to adopt circular economy practices and reduce their plastic consumption. In collaboration with the UN, the Global Commitment has united more than 500 organisations behind a common vision of a circular economy for plastics. Companies representing 20% of all plastic packaging produced globally have committed to ambitious 2025 targets in tackling plastic pollution at its source.

The L&D (loss and damage) fund illustrates a consensus that climate change is going to be a very costly issue, and this is not just about the countries that cannot afford it. Developed markets are going to have to fund their own way through natural disasters.

It is disappointing that COP 27 did not join the dots on this with more ambitious targets, or more details on how to reach these goals. However, we are encouraged by the behind-the-scenes commitments and believe accelerating decarbonisation will create unprecedented investment opportunities. From our perspective we see climate stakeholders increasingly make changes independent of multinational initiatives