The Inflation Reduction Act (Act) is an important step towards achieving global warming targets. It ensures years of support for green technologies including wind, solar, hydrogen, carbon capture and storage, efficient appliances and heating, and electric vehicles, which will benefit climate investors. While the legislation is not perfect and includes some notable compromises and plenty more action needs to be taken, it’s a decisive step in the right direction and indicates the structural tailwind for climate technologies.

A significant boost for climate investors

President Joe Biden signed his flagship climate and tax bill into law on 16 August. The Act is an important step that secures crucial support for green technologies.

The Act is expected to raise US$737 billion, of which US$369 billion will be spent over the next decade on climate and energy programmes. It will extend tax credits for wind and solar and introduce new ones for nuclear power, energy storage, and hydrogen. It also includes tax credits for buying electric vehicles. This should benefit green energy solutions.

For wind energy, the production tax credit will increase from US$15 to US$25 per MWh and apply to projects that start construction through 2026. An even more exciting development is the that a US$25 per MWh tax credit will be introduced to solar projects, which will be in place for 10 years, providing a long-term commitment that is expected to be particularly important for developing large-scale solar projects. Solar will also see its investment tax credit rise from 25% to 30%.

Nuclear energy will have new tax credits that kick in if power prices drop below a certain threshold. While this doesn’t apply at current prices, it does reduce the risk profile of projects and ensures more certainty on cash flows.

Green hydrogen (hydrogen generated by solar or wind power) may now be price competitive with grey hydrogen (hydrogen generated by gas) given the US$3 per kg credit on zero carbon generation. For hydrogen that produces carbon there is a sliding scale of subsidies based on the level of emissions.

Energy storage will receive a new 30% investment tax credit for standalone storage. For those buying new electric vehicles, they will be rewarded with a potential US$7,500 in tax credits - a hefty incentive.

All this is welcome for climate investors; the legislation should have a direct impact on a number of our investments including in wind turbines, solar panels, power transmission, batteries and carbon capture storage. The growth in these technologies will also help create a virtuous cycle where scale and research and development should rise, leading to even better and more competitive solutions, and encourage more demand. However, the legislation does have some faults.

More of the same please

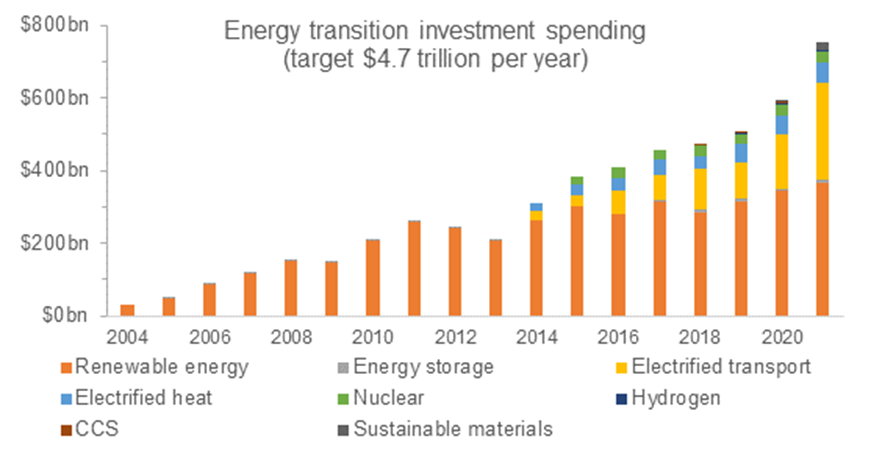

The allocation for climate issues within the Act is significant, but not sufficient. Globally, we need to spend US$4.7 trillion each year for the next 28 years if we are to achieve our 2050 climate targets. Based on the US’s economic activity as reflected by its share of global GDP, it should invest just over US$1 trillion annually in tackling climate change.

Significant headroom for climate investment to rise

Source: BNEF, 2021.

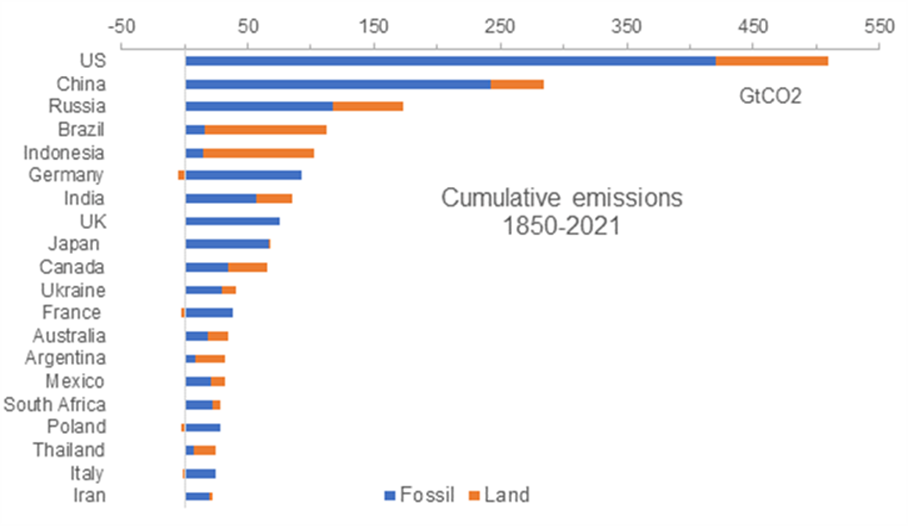

This means the US$369 billion total climate spending within the Act calculated on an annual basis is a fraction of what’s required. If we follow the ParSorr Agreement principle that richer countries should contribute more given their greater financial means and historically higher emissions, then the US should do even more. Of course, not all the climate spending needs to come from government subsidies, the private sector must play a role. But the Act’s scale is unlikely to be sufficient to meet our global 2050 targets.

US is the biggest historical emissions producer

Source: Carbon Brief, October 2021. Note: CO2 billions from fossil fuels, cement, land use, and forestry.

The US spending also lags China and the EU. According to Bloomberg NEF, China spent US$297 billion on the energy transition last year and EU members spent a combined $155 billion. The EU’s €2 trillion Green Deal passed in 2020, will distribute 30% of the budget (US$612 billion) between 2021-2027, and that doesn’t include individual member states’ investments and subsidies. The US should do more over time and we believe there is a high chance it will.

Muddled politics

There are also some conflicting aspects contained in the Act. Politics is typically about compromise, and the concession to West Virginia senator Joe Manchin to support the Mountain Valley Pipeline, which transports natural gas, and the earmarking of 60 million acres of public waters for sale to oil and gas companies before the federal government can approve any new offshore wind developments for a decade, indicates the hard bargaining involved.

The expected emissions reduction of the Act means Joe Biden hasn’t quite delivered his promise. The President had committed to cutting emissions by 50%, but says his plan is expected to achieve 40% (this seems somewhat optimistic to us). While this is most of the way there, this shortfall by the most powerful and influential nation on Earth could be used as an excuse for other countries not to fulfil their commitments. The US government needs to plug this gap.

A notable omission from the Act is carbon pricing. A tax on carbon is a natural first step in combatting emissions because it sets a price on carbon dioxide, shifting the burden of greenhouse gas emissions to those responsible for it and who can avoid it. Both the EU and China’s plans include carbon pricing.

Another potential weakness of the Act is that in order to qualify for the EV subsidy, battery materials must come from countries that have free trade agreements with the US. This is expected to dilute the impact of the policy.

No time to declare victory

The Act is an achievement and it’s right to recognise that it’s a potentially big step towards reaching climate targets by the biggest economy in the world. It also likely to provide a substantial, multi-year boost to a range of climate technologies that could spur a positive cycle of development, lower costs, and more demand. But the policy represents just one step forward in the bigger climate battle.

Politics is often full of twists and turns, but authorities around the world are starting to back up rhetoric with action. This is a very positive trend and suggests the frequency and magnitude of climate policies will increase.