The world’s largest bloc of emerging market economies is getting bigger by six, with expanding membership of BRICS hinting at aspirations of a new world order. But with one country - China - continuing to pull far more economic weight than everybody else, we think the significance of the forthcoming BRICS expansion will be more diplomatic than economic.

Meet the new bloc…

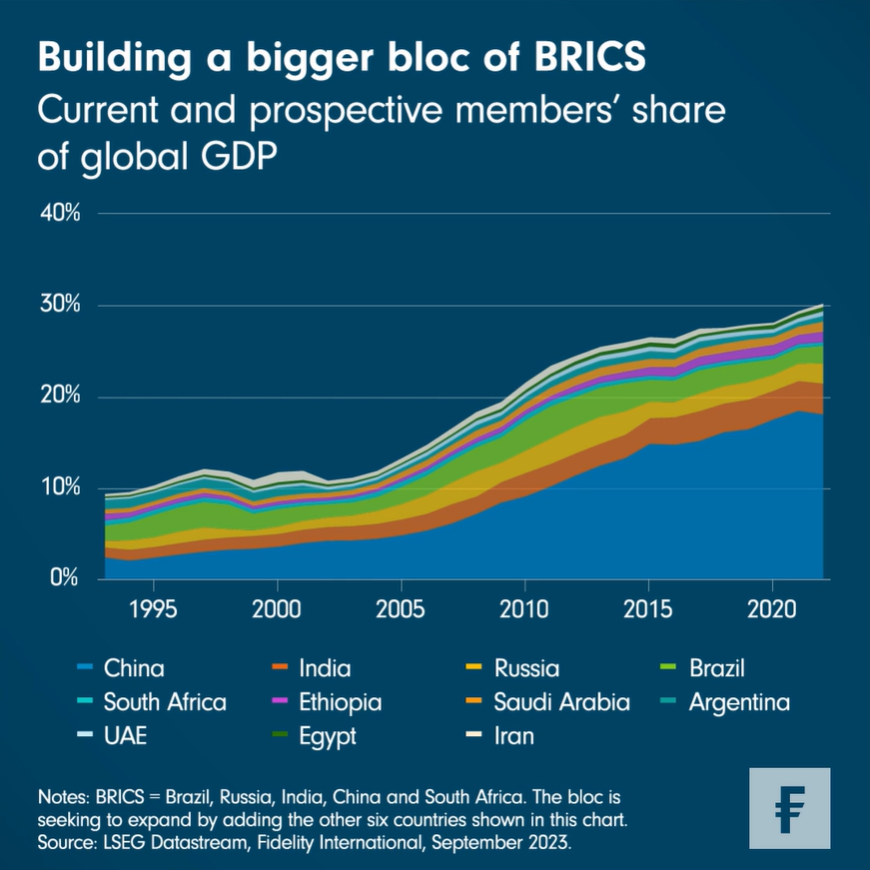

Mercifully few economic acronyms last for long (remember CIVETS?). Fewer still find renewed relevance over time. BRICS, standing for Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa, has so far proven to be an exception. The group recently announced its intention to add Argentina, Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates to its ranks. The news hints of aspirations for a new economic order, as the expanded bloc’s combined share of current world GDP, at about 30 per cent, is closing in on the G7’s shrinking slice of the pie (43 per cent). And it’s roughly triple what it was back in 2001 when then Goldman Sachs economist Jim O’Neill first coined the term BRICS.

Same as the old bloc

But take a closer look, and the new BRICS looks a lot like the old one. China’s 18 per cent share of global GDP, up from just 3.9 per cent in 2001, dwarfs everybody else’s. This week’s Chart Room plots the changes over time in share of world GDP. It shows how India (now at 3.3 per cent), Brazil (1.9 per cent) and Russia (2.2 per cent) have made only very modest gains in the past two decades while South Africa, which was added to the group later, has maintained its sliver of global output (0.4 per cent). Assuming all six new invitees will join, they bring to the table a combined 4 per cent of global GDP (Argentina’s membership is uncertain, as both leading candidates for October’s presidential elections are opposed).

Won’t get fooled again

The BRICS also want to de-dollarise - both among themselves and with their trading partners - while exploring new intra-BRICS options for cross-border payment systems or correspondent banking relationships, according to the joint declaration from their August summit. But these things are harder done than said while the US dollar accounts for 59 per cent of global reserves and half of world trade, according to Bank of International Settlements data. The Chinese renminbi is the only BRICS currency with a big enough share of allocated global reserves (2.6 per cent) to be reported independently outside of ‘other currencies’ by the International Monetary Fund; the rest are G7 currencies. None are likely to threaten dollar dominance for at least a generation. Not to mention the BRICS’ share of world trade, at 16 per cent, is less than half that of G7’s (33 per cent).

My generation

Where the new BRICS can move the needle is in providing a greater voice to the ‘Global South’ when it comes to issues of multilateral diplomacy. With the exception of United Arab Emirates, the poorest G7 nation (Japan) is better off than every member of the expanded BRICS, in GDP per capita terms, according to World Bank data. It may seem an understatement of the obvious, but the economic and political priorities of developing countries (like the BRICS) and the richest countries (like the G7) are not always in line. For example, big differences have emerged recently over everything from the war in Ukraine, to global decarbonisation targets, to representation on the UN security council. While O’Neill originally saw BRICS as an economic phenomenon, today it looks increasingly like the block’s heft is swinging towards the diplomatic arena.