Geopolitical tensions and evolving security priorities have pushed defence up the investment agenda, challenging assumptions shaped by decades of the “peace dividend”. European governments are now rebuilding capability on a sustained basis, marking a material change in the outlook for the sector. Against this backdrop, understanding how defence fits within sustainable investment frameworks has become increasingly important.

Key points

- Defence spending in Europe has entered a structural upcycle driven by a more fragmented geopolitical environment. This represents a sustained shift rather than a short-term reaction, materially improving revenue visibility and long-term demand for the sector.

- The defence sector has broadened well beyond traditional weapons manufacturing. This creates less obvious defence exposure in portfolios and complicates how investors assess alignment with sustainability mandates.

- Rather than binary inclusion or exclusion, disciplined frameworks and transparent governance are critical for managing reputational risk and aligning defence exposure with client objectives.

A structural shift in global defence spending

For much of the period since the end of the Cold War, European defence budgets have declined, with defence policy shaped by the assumption of a relatively stable geopolitical environment. That assumption no longer holds. Europe’s defence landscape has moved decisively away from the “peace dividend” mindset that deprioritised defence due to perceived low security risks.

Defence budgets across Europe are now rising, in what appears to be a sustained shift rather than a short-term response. The European Union’s Readiness 2030 and ReARM Europe programmes together aim to mobilise more than €800 billion in spending over the coming years. NATO allies have committed to allocate 5% of GDP to defence and security by 2035, including a new 3.5% guideline for core spending. These targets are not binding, and political support remains uneven, but they point to a clear change in direction.

Geopolitical tensions trigger a shift in attitudes towards financing conventional weapons

Compared to conventional weapons, ongoing exclusions of controversial weapons (e.g. cluster munitions, anti-personnel mines, biological / chemical weapons) have not seen the same level of debate and are more commonly excluded from sustainable investing funds.

Source: Fidelity International, 2026

Political developments have reinforced this trajectory. Questions over the durability of the US security guarantee have prompted European governments to prioritise greater strategic autonomy and invest in domestic capabilities. At the same time, recent conflicts have exposed gaps in stockpiles, supply-chain resilience and operational readiness, accelerating procurement across both traditional equipment and more advanced technology systems.

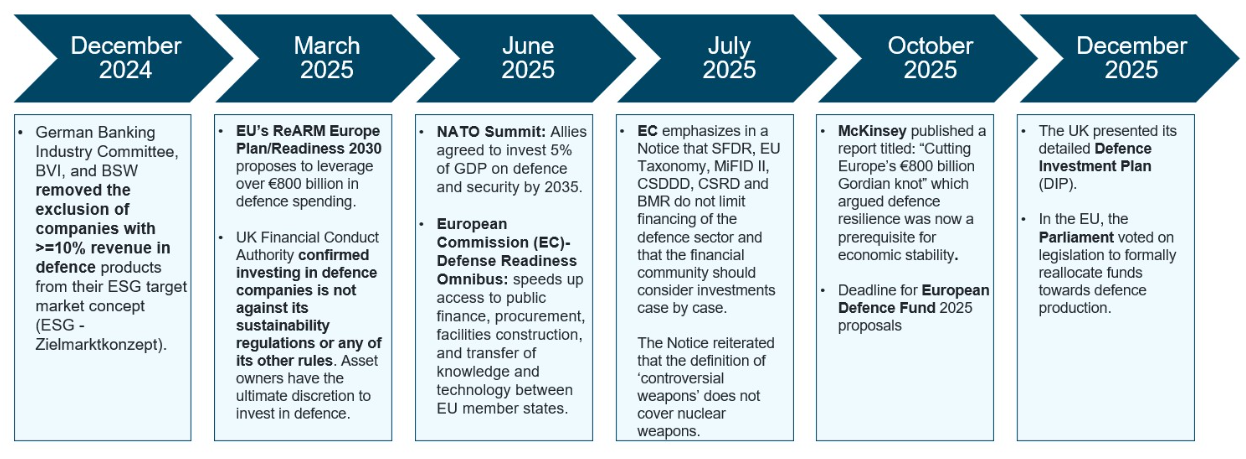

Regulatory attitudes are beginning to reflect these shifts. In December 2024, for example, Germany removed industry guidelines that had prevented companies deriving more than 10% of revenue from defence activities from inclusion in sustainable funds. Given Germany’s historically conservative approach, this change could be indicative of a wider reassessment of how defence aligns with long-term industrial and sustainability objectives across Europe.

How the sector is evolving and why it matters for investors

These forces are reshaping policy and, in doing so, transforming the structure of the defence sector. Modern defence activity spans a broad ecosystem of capabilities, many of which sit within the private sector. Companies providing cybersecurity, satellite networks, secure communications, simulation technologies and logistics are now integral to national security operations. Many of these businesses are not classified as defence companies but have become central to government strategies as security challenges evolve.

This broadening of the sector has several implications for investors. Defence-related exposure may now appear in portfolios in less obvious ways, embedded within aerospace, industrials, infrastructure and technology holdings. Sector growth is increasingly tied to digital and resilience-related capabilities, rather than solely to traditional hardware.

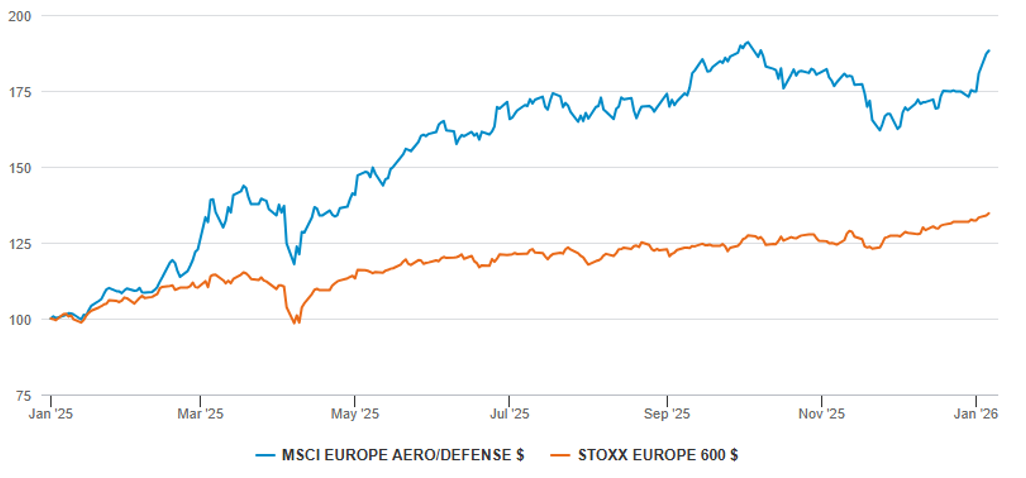

In addition, prolonged defence sector outperformance has created performance headwinds for ‘dark green’ portfolios with longstanding underweights, underscoring the importance of how defence exposure is considered within sustainability-aware mandates. Since early 2022, European aerospace and defence companies have outperformed the broader equity market, supported by stronger order books, clearer policy direction and improved revenue visibility.

European defence has outperformed in 2025

Source: LSEG Datastream, Fidelity International, January 2026

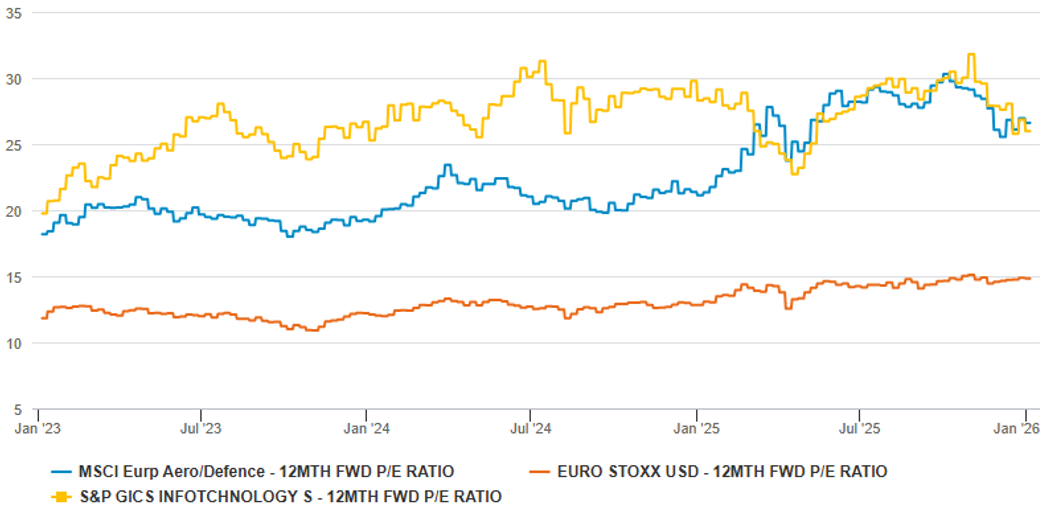

European defence valuations now similar to US tech

Source: LSEG Datastream, Fidelity International, January 2026

As the sector continues to evolve, the key consideration for investors is how defence exposure aligns with their sustainable investing objectives, reputational risk, and client preferences.

Sector outlook

The medium-term outlook for defence companies reflects the structural nature of these shifts. NATO and EU commitments indicate multi-year requirements for equipment, technology and industrial capacity. This creates a more resilient revenue environment for companies across the sector and reinforces defence as a long-term strategic theme.

A major consideration is whether companies can scale capacity to meet rising demand. Years of underinvestment have meant that many defence manufacturers face production bottlenecks and reliance on complex supplier networks, which may influence delivery timelines, cost structures and the pace at which policy commitments translate into revenues.

Moreover, despite the strength of current demand, the sustainability of higher spending is not uniform across Europe. While momentum is strong, fiscal headroom is limited in many countries and public support for sustained increases varies widely. Several governments have announced ambitious targets, yet some are relying on reclassifications, or temporary funding mechanisms, rather than genuine budget expansion. This suggests that growth may be concentrated in countries with stronger balance sheets and clearer political commitment, such as Germany, the Nordics and parts of Eastern Europe, while other regions may struggle to maintain elevated spending over the long-term.

Why an ESG lens is becoming increasingly important

As defence becomes a more prominent consideration, investors face greater scrutiny over how holdings reflect their sustainability commitments and investment objectives. Some prioritise complete avoidance of particular activities, while others are open to exposure where companies can demonstrate strong governance, credible oversight and responsible management of end-use risks. Recent conflicts have sharpened attention on these issues, particularly the role of defence in safeguarding national sovereignty. This has increased the need for clarity around how defence companies manage their operations and supply-chain relationships.

Many of the operational challenges translate directly into material ESG risks. Complex supplier networks, the use of intermediaries, lack of clarity on specific products or weapons produced, and the difficulty of verifying end-use mean that accountability can be challenging to establish. These considerations influence not only how companies operate, but also how investors assess responsible practice and potential reputational exposure.

The growing role of emerging technologies, including autonomous systems and AI, adds further questions around dual-use applications and corporate oversight. As a result, nuanced analysis becomes central to determining when, and under what conditions, the sector can be considered aligned with a sustainable portfolio’s investment objective and end clients’ preferences.

How sustainable funds typically treat the sector

These complexities help explain the varied treatment of defence within sustainable strategies. Controversial weapons, including cluster munitions, anti-personnel mines and chemical or biological weapons, are widely excluded from funds with binding ESG characteristics, which is in line with international conventions. Nuclear weapons occupy a grey area: some investors classify them alongside controversial weapons, while others permit limited exposure under non-proliferation frameworks.

Approaches to conventional weapons vary. In Europe, many Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR) Article 8 funds retain exposure, while Article 9 funds typically apply stricter exclusions. The complexity deepens when considering how involvement is defined. Some asset managers exclude only manufacturers; others exclude distributors, service providers or producers of dual-use components. Recent debates around the use of civilian machinery in conflict zones illustrate how difficult it is to apply universal definitions. Even companies such as Rolls-Royce, traditionally associated with aerospace engineering rather than weapons systems, appear in some exclusion lists depending on how data providers classify their components and support services.

Market behaviour reflects these complexities. Most Article 8 funds do not exclude companies involved in conventional defence, and more than half maintain some exposure. Only a minority apply explicit exclusions. These trends highlight the role of investor judgement and the importance of credible governance frameworks in an area where definitive classifications are difficult to consistently apply.

Providing clarity, governance and consistency

Against this backdrop, Fidelity’s priority is to provide structure, transparency and consistent governance, rather than advocacy. Our approach incorporates:

- Activity-based exclusions, applying revenue thresholds for specified weapons categories across our ESG Unconstrained, ESG Tilt and ESG Target funds with firmwide exclusions for controversial weapons.

- Conventional weapons exclusions, applied only within the most sustainability-focused strategies, primarily Article 9 and a small number of Article 8 funds, which apply under the SFDR.

- Norms-based exclusions, which assess company conduct against recognised international standards on business ethics, human rights and environmental behaviour. Providers often differ in how they classify controversies, reinforcing the importance of our internal reviews.

- Oversight through the Exclusion Advisory Group, ensuring consistent interpretation when data diverges, or where involvement requires judgement.

- Sovereign exclusions, incorporating governance quality, sanctions exposure and broader political risk.

Our integrated research model combines fundamental and ESG analysis to form a holistic view of exposures. This allows us to support clients whether they wish to include defence companies, avoid them entirely, or understand how exposure aligns with their mandates. The aim is to provide a neutral, evidence-based approach that helps investors navigate the complex trade-offs inherent in balancing financial and sustainability objectives.

Navigating a nuanced landscape

Defence now sits at the intersection of geopolitics, regulation and sustainable investing. Structural spending commitments are reshaping long-term demand. Private sector partners are becoming more deeply embedded in national security strategies. Regulatory guidance is prompting more nuanced treatment of defence within sustainable portfolios. At the same time, the sector’s ESG challenges - particularly around governance, social impact and end-use - remain fundamental.

For investors, the landscape is defined by nuance rather than binary choices. As global security challenges persist, the debate around defence and ESG will continue to develop. In this environment, disciplined analysis and consistent frameworks are crucial to aligning investment decisions with long-term objectives, client expectations and sustainability priorities.