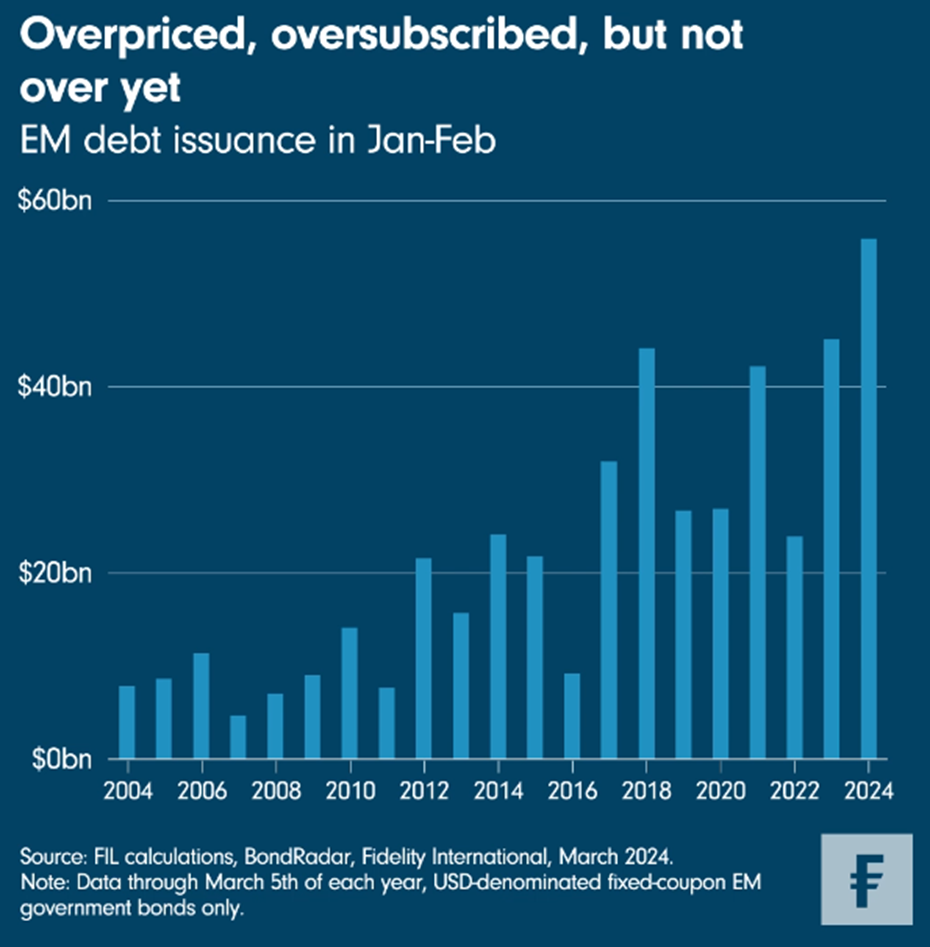

Developing world governments borrowed as much in January and February of 2024 as they did in the same period of any of the last 20 years. And yet all indications are that a jump in investor interest in emerging credit and debt is just getting going.

Price is $USD

If you needed any convincing that 2024 will be the year when investors turn en masse towards credit, then look no further than the issuance in the first two months of the year. The assumption after December that the US Federal Reserve was done raising interest rates has been the trigger for an avalanche of interest in a wide range of higher-yielding bonds and credit. Spreads across the board have tightened with one popular indicator in the emerging markets space, the JPM EMBI Global Diversified 'spread to worst', tightening over 80 basis points since October.

This Chart Room shows how emerging market (EM) governments have responded with the biggest splurge in dollar-denominated debt sales in 20 years - some US$56 billion. Even after this flood of supply, demand from asset managers is still four times the offer amounts for most of these new bonds.

Behind those stark numbers there are three trends worth noting. Firstly, at the same time as all the issuance, emerging market (EM) funds have been seeing outflows. Why? Retail investors may still be reluctant to shift into emerging markets, given memories of post-Covid EM sovereign defaults that contrast with the perceived safety of cash and US equities.

Some weaker borrowers who didn’t have access to markets last year, such as Ivory Coast, Kenya, and Montenegro, have already successfully issued bonds this year. More stressed countries such as Nigeria and Egypt are also likely to test the market in the weeks ahead, giving us more signals to work with.

But if EM funds are not buying EM assets, then who is? This is what seem to be trends two and three: cross-asset investors chased out of developed market investment grade segments due to the extraordinary tightening of spreads (itself driven by a surge of inflows) are buying EM debt. Thirdly, domestic investors in increasingly wealthy home markets like Eastern Europe or the Middle East are choosing to flex their financial muscles locally and diversify their fixed income holdings.

These last two trends suggest demand for both sovereign and corporate credit across the emerging market universe is unlikely to abate. It raises the question - do markets find themselves in a situation similar to that which existed in the lead up to the Global Financial Crisis, where there wasn’t enough credit supply to go round? We know how that ended.

More immediately, and while taking a breath at what are increasingly heady valuations across the board, the crowding out of some markets may soon push investors further down the quality spectrum in search of value. If the Fed moves ahead - or signals clearly when it will move ahead - with interest rate cuts that reduce returns on cash, that may make investors only more eager to look at emerging market bond funds.